Unpacking Australia's per capita recession

Australia's per capita recession is the inevitable consequence of past policy decisions, where attempts to curb inflation clash with the need for economic stability, leaving households and young people bearing the brunt of a painful economic adjustment.

It's national accounts day today, which is why you would have seen plenty of Treasurer Chalmers on the media circuit, pointing fingers in all directions except his own:

"With all this global uncertainty on top of the impact of rate rises which are smashing the economy it would be no surprise at all if the national accounts on Wednesday show growth is soft and subdued.

We anticipated a soft economy at Budget time and that's what most economists now expect to see in these new numbers for the June quarter.

We are striking all the right balances between a primary focus on inflation and understanding the pressures on people in an economy already being hammered by higher interest rates and global volatility."

The June quarter national accounts will probably show that real GDP per person contracted for a fifth consecutive quarter, officially making the current period Australia's worst and longest per capita recession since the 1990-91 "recession we had to have" (excluding the pandemic).

We're not in a technical recession (GDP contracting over two consecutive quarters) largely because population growth and "strength in public demand" are keeping total activity churning along. But even that looks set to have weakened in the June quarter to around 1% growth from a year ago, according to Bloomberg.

Chalmers isn't entirely to blame for the state of the economy. When the previous Coalition government and the states closed their borders, locked us down, and enforced social distancing, they reduced economic activity and paid for it with debt, much of which was bought (electronically printed) by the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA). That boosted demand and reduced the value of the currency relative to goods and services, causing the inflation.

As a recent paper concluded, supply chain issues were only a secondary factor (in that they constrained economic activity), with the post-pandemic inflation "predominantly driven by unexpectedly strong demand forces", i.e. excessive fiscal and monetary policy.

Once set in motion, an aggressive attempt by the central bank to rein it back in would have "severely hampered an already anaemic recovery".

So, a lot of the damage was baked in before Chalmers took office. Indeed, one reason this cost-of-living crisis feels so bad is because we had it so good for a couple of years. It may have all been an illusion, but that doesn't change the fact that returning to a more sustainable path was always going to be painful; bouts of inflation always end up with prolonged reversals of the inflationary trend, which is costly.

A painful reversion

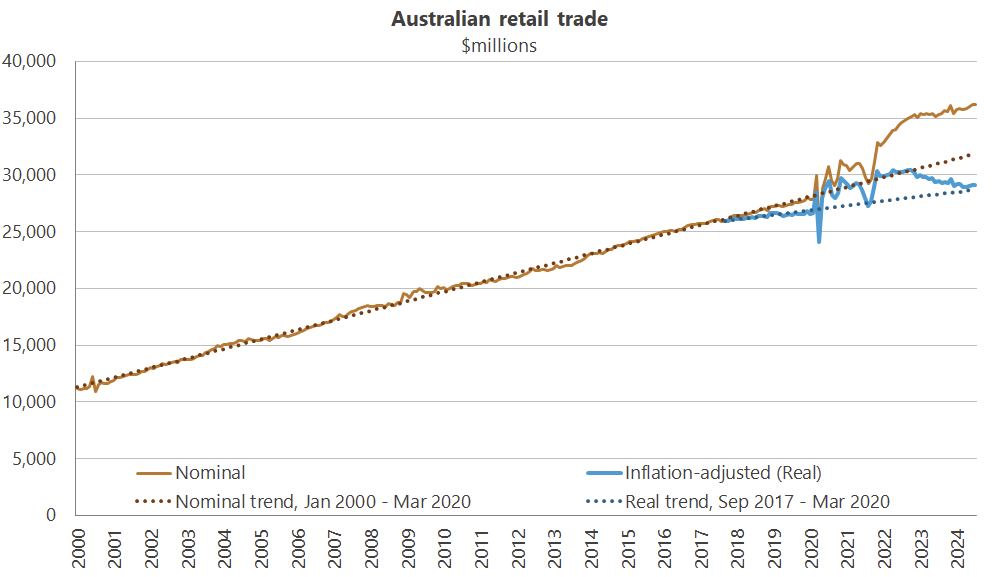

A look at last week's retail turnover figures show that after a considerable increase in household's real purchasing power, sales are now back to where they were before the pandemic:

The story is even worse for incomes. We didn't get any wealthier from all the debt-financed handouts during the pandemic while also working fewer hours; there was no miraculous surge in productivity that led to a sustained increase in real purchasing power.