Should we be worried about the US?

While the US economy is hitting all the right notes—low unemployment, stable inflation, and strong wage growth—massive deficits and reckless policy proposals could tip the scales.

I started writing a post on the upcoming US election and what it means for Australia, but of course it was shaping up to be way too long for a single email. So, here's the first of what will be a two-part post on whether we (Australia) should be worried about the US.

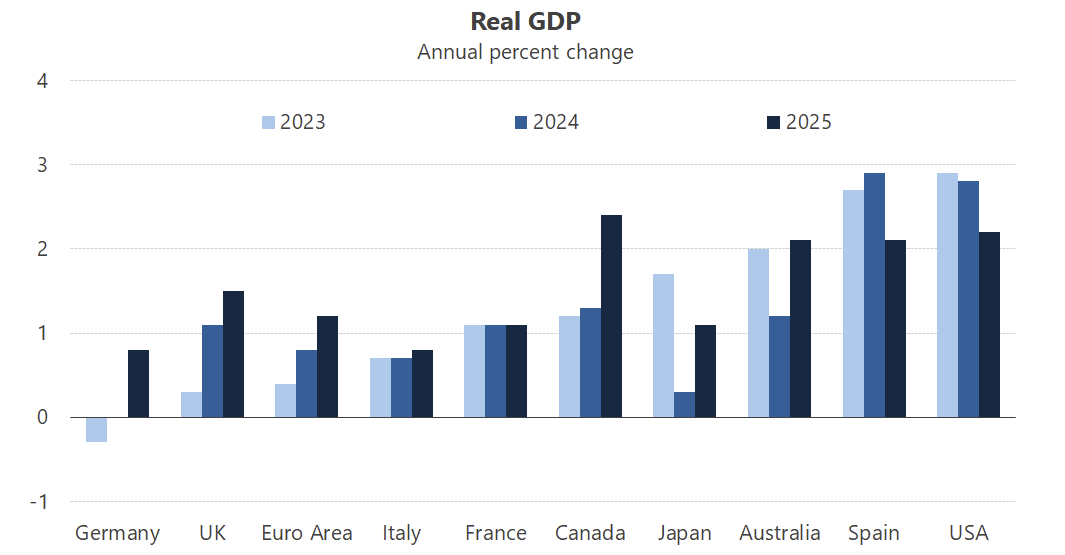

This might seem like an odd time to write a post with this title, given the US economy is humming. It is, by a long way, the best-performing economy since the pandemic, and the IMF's latest World Economic Outlook projects that trend to more or less continue:

As blogger Noah Smith recently observed:

"Essentially, there are four things you want from a macroeconomy:1. You want high employment rates, so that everyone who wants a job has a job.2. You want low and stable inflation rates, so that people know how much a dollar will be worth a month from now.3. You want fast wage growth, so that regular working people are taking home their share of economic growth.4. And you want fast productivity growth, because ultimately that's what creates durable gains in living standards.Right now, the U.S. economy is giving us all of those things."

Smith was careful to point out that the US government is also running recurring deficits at about 6.5% of GDP, which are "unprecedented outside of war or severe recession". To the extent that's what's driving its recent macroeconomic success, he warned that "eventually there will be a reckoning".

But it was only when The Economist magazine dedicated a glowing cover to the US economy that I really started to consider that the day of reckoning might be closer than first thought:

You see, The Economist has a notoriously poor record at forecasting. If you had bet in-line with the positions implied by its covers, after a year you would have lost, on average, around 10% of your investment:

"The reversal starts pretty much right after the cover comes out (on average) and is strongest about a year later. The bearish covers are a stronger signal because most assets have been in a huge up trend since 1997. The fact that the bullish magazine covers yield meaningful bearish results is absolutely amazing in the context of the 'bubble in everything' that has prevailed since 1997, when the Greenspan put was born. Most of the assets studied here have skyrocketed since 1997, so to find an indicator that yields meaningful bearish results is highly significant to me. I have done many, many of these types of studies, and the trend of the assets in question often dominates the output. Not here."

So, is the US economy about to tank, or has The Economist got one right for a change? I'm not going to pretend to know the answer, but with a pivotal US federal election less than two weeks away and several economic indicators flashing big, bright warning lights, there's a reasonable chance that The Economist may have done it again.

The elephant in the room

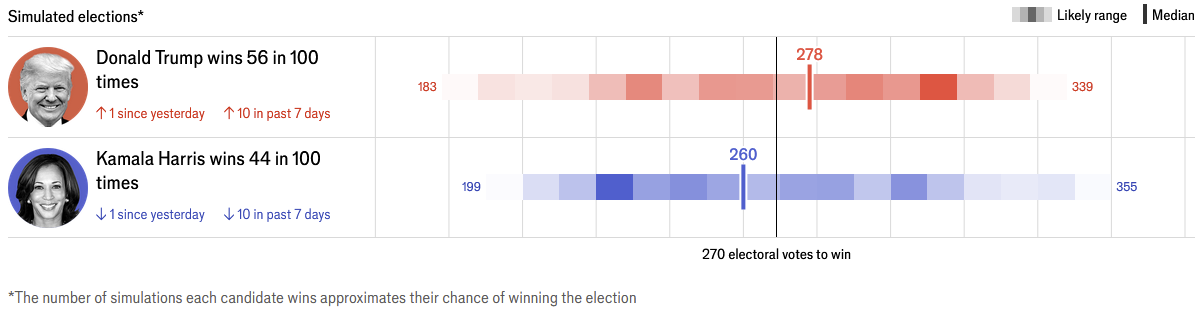

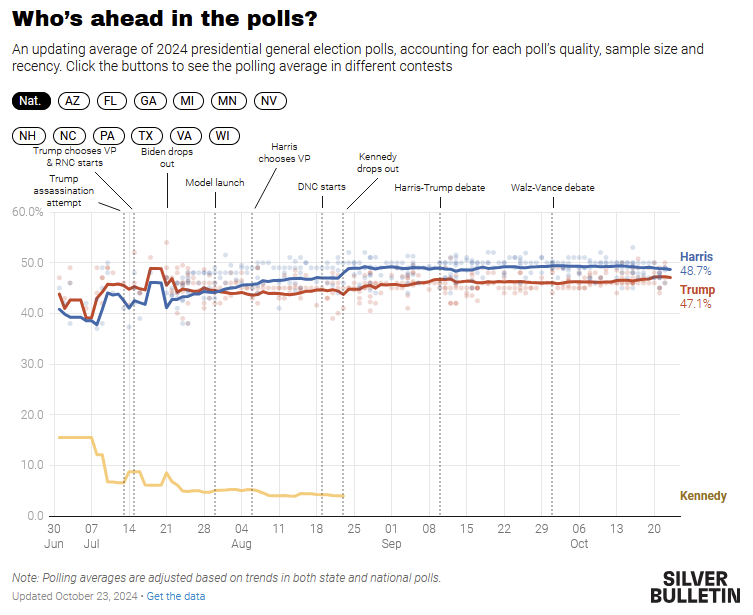

In the US political system, the Democrats are represented by 'stubborn donkeys' and Republicans by 'brave elephants'. And there's no bigger elephant than Donald Trump, who now leads Kamala Harris on both polling and betting markets. Here are a couple of the latest polling simulations:

Polls can also be a bit misleading because in the US, the election is not decided on the popular vote but by the Electoral College system. Recent history suggests that the Democrats need to win about 52% of the two-party popular vote share to form government.

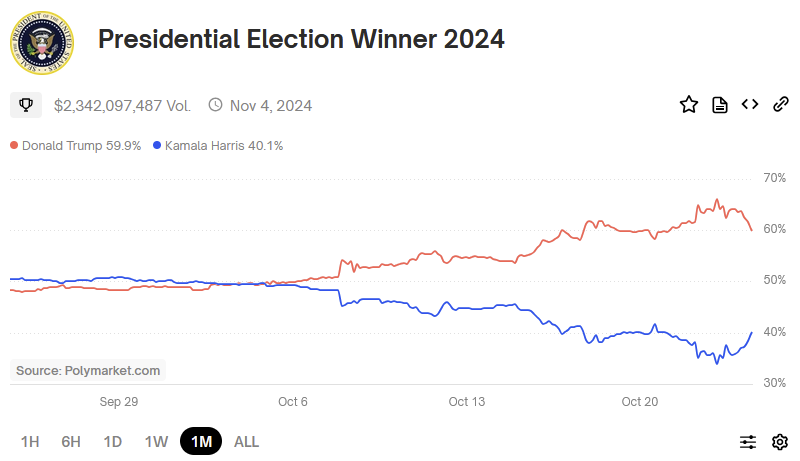

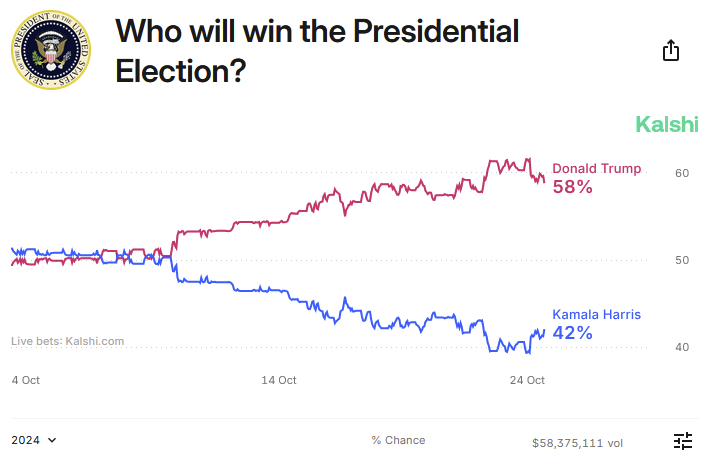

My preferred place to look for answers is on betting markets, where the results aren't derived from people who still answers phone calls from pollsters but by those putting real skin in the game. Here are the latest odds from a couple of the most well-known betting markets:

The odds might look good for Trump, but you must remember that odds are not polls, and odds of 40% still represent a strong chance of victory. So, right now it's basically a toss-up between the two.

So, less than two weeks out and it's still anyone's race. But while both Trump and Kamala look set to continue with highly stimulatory fiscal policy, a Trump 2.0 administration seemingly has larger implications for Australia, most notably because of his economically illiterate views on everything from central banking to trade.

Trump's stated position is to add a tariff of 10 percentage points on all US imports, while imports from China would all rise by 60 percentage points. As justification, he claims that:

"The higher the tariff, the more likely it is that the company will come into the United States, and build a factory in the United States so it doesn’t have to pay the tariff."

The empirical evidence shows tariffs are most harmful for the countries that impose them, with a general rule of thumb that:

1. Roughly 15% of a tariff is borne by exporters from the other country.

2. Another 15% results in compressed margins for American importers.

3. 70% of the burden is borne by consumers paying higher prices.

They also don't tend to encourage capital formation or increase employment in the affected industries, because while they raise the cost of international competitors' goods, they also increase the cost of imported intermediate goods for domestic producers. And US trade happens to be dominated by that effect, with well over half of imports falling in the intermediate category.

The low bar for economic policies

Trump has some other truly insane policies too, such as ending taxes on overtime and tips (Harris also supports that one). Both are highly distortionary and would effectively force people to restructure their employment to be as tip-based as possible, or start working extremely long hours to rack up as much overtime as they can without dropping dead.

Trump also wants to cap interest on credit cards at 10%, a policy straight out of the playbook of Elizabeth Warren. It's basically a price control and would function as all price controls do: by forcing the suppliers of credit cards to ration credit. The worst off would be those most at risk of not paying their debts, i.e. the poor, who would likely be forced to use other much shadier options, such as loan sharks.

Harris is almost as bad, but in different ways. She wants to crack down on "price gouging", and tax unrealised capital gains. She's also a fan of regulation and antitrust, especially for the nation's big tech companies, which would ultimately shift the US economy closer towards a safety-first, less-innovative and less-productive European model. Harris has also proposed to 'solve' housing with a huge national first home buyers grant, something that we're all-too-familiar with in Australia (repeat after me: demand stimulus in supply-constrained markets doesn't work!).

That's most of the worst stuff out of the way. They both have some positives, but because of how the US constitution is structured, it's questionable whether they'll even be able to implement them: the President has the power to do things like impose tariffs with executive orders only because Congress has granted the executive that discretion.

For most other policies, they need to be negotiated.

For example, Kamala Harris wants to codify Roe v Wade (federal abortion rights), but she's not likely to be able to get the support of the Senate without ending the filibuster, which would reduce the required votes from 60 to 51 (i.e. a simple majority). But there's limited support for doing that – even among Democrats – because "eliminating the filibuster to codify Roe v Wade also enables a future Congress to ban all abortion nationwide".

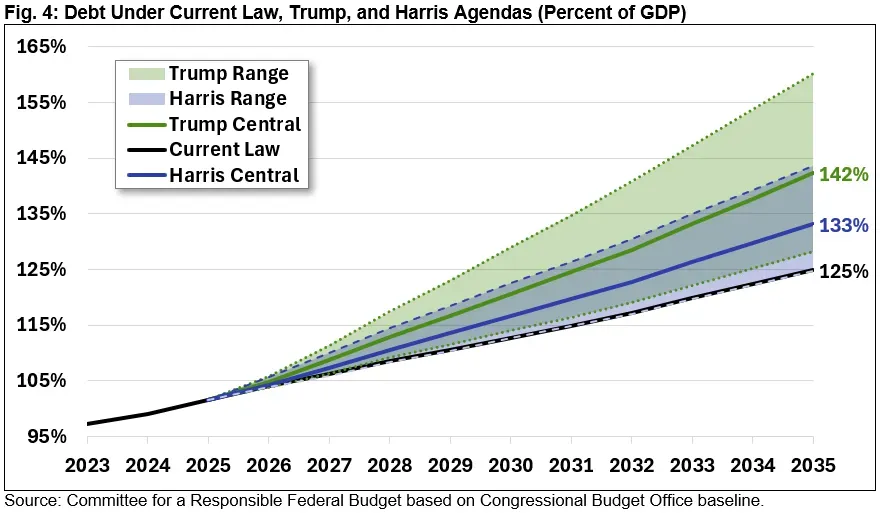

As for Donald Trump, many of the economically positive things he wants to do – e.g. cutting the corporate tax rate to 15% and extending the 2017 temporary tax provisions – will face similar Congressional roadblocks. And they might even be harmful when considered as a whole, rather than in isolation: if his tax cuts were passed after even one of his other distortionary tariff or tax changes, they could end up decimating an already-precarious budget, bringing forward legitimate questions about fiscal solvency and the dreaded "reckoning".

On the flip side, the difficulty of getting laws through Congress means that many of the candidates' most damaging ideas, such as price controls and taxes on unrealised capital gains, are unlikely to ever see the light of day.

A fragile budget without solutions

Speaking of fiscal room, neither candidate has really said anything about spending, other than that they plan to keep doing a lot of it. What they have revealed is that they won't touch the two biggest budget-busting line items: social security and Medicare.

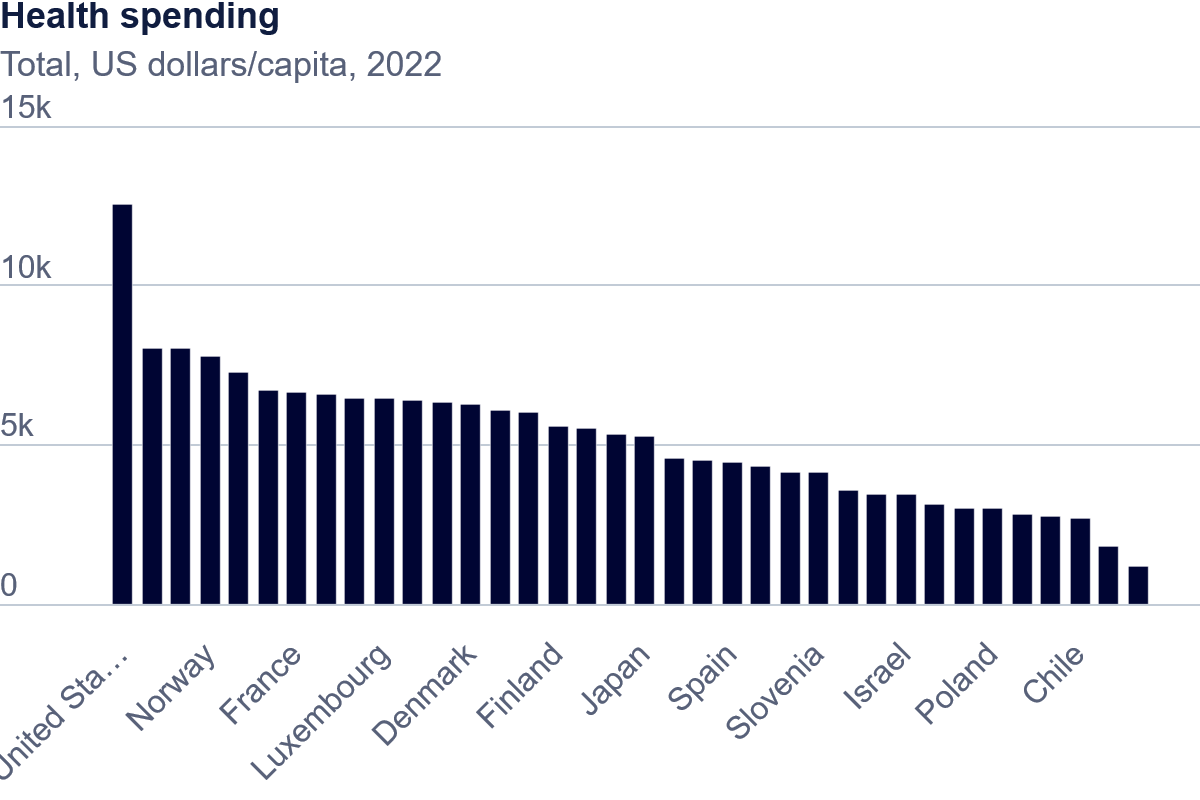

In fact, they want to expand them: Trump's policies would shorten the remaining life of the social security trust fund by a third, while Harris would expand Medicare outlays by also including long-term, at-home care services. This, in the country that already spends significantly more on healthcare than any other nation:

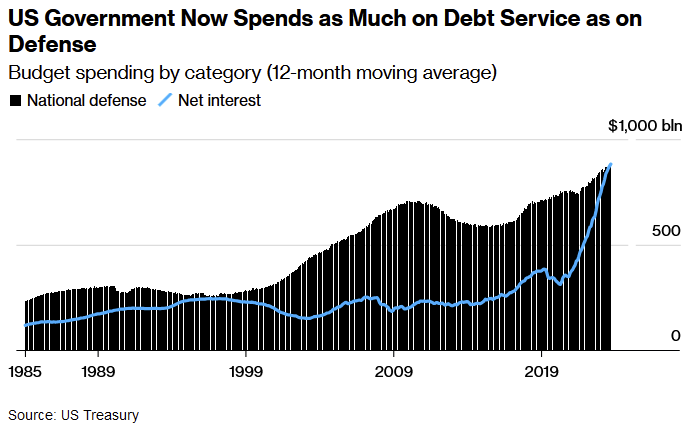

It's all well and good to have such ambitious spending proposals, but neither candidate has any real plan of how to pay for them, other than with more debt. And that approach is clearly unsustainable, with interest payments alone fast approaching 30% of all government revenue. Interest payments also recently surpassed defence spending for the first time, violating historian Niall Ferguson's "vulnerable empire" threshold:

That ever-growing debt burden crowds out the private sector at an estimated 33 cents on the dollar, but also crowds out the government itself: just 30% of spending today is discretionary, down from 70% in the 1960s, leaving whomever wins the Presidency with fewer and fewer resources with which to finance their grand policy proposals.

But what they can do is regulate. Trump has said he'll appoint Elon Musk to a new Department of Government Efficiency (the acronym is even the same as Musk's favourite cryptocurrency, DOGEcoin), and Elon has said that Trump 2.0 represents "an opportunity to do kind of a once in a lifetime deregulation and reduction in the size of the government".

Given that the time it takes to start a business in the US has nearly doubled in the past fifteen years, there's probably plenty of efficiency that can be eked out of the US economy simply by removing red tape. However, your guess is as good as mine as to how it works out. I'll just say that Trump is notoriously combative with his own people and failed pretty badly at "draining the swamp" the last time around, so I do wonder how long Elon will last. Tweaking regulations and trimming the bureaucracy is also not even going to come close to solving the country's structural budget problem.

As for Harris, she is a keen regulator who will almost certainly continue with the Biden administration's approach: namely, to expand Washington's influence over labour markets, the environment, finance (including crypto), and big tech.

Phew! Anyway, returning to The Economist, perhaps the most glaring contrarian indicator of "peak USA" in its feature was this factoid:

"Mississippi may be America's poorest state, but its hard-working residents earn, on average, more than Brits, Canadians or Germans."

Mississippi is a state that has seen no growth since 2014. At least a quarter of its "hard-working" residents' income now comes in the form of transfers from the federal government, effectively funded with debt. And it's not alone: the share of the country reliant on government transfers for a quarter or more of total personal incomes has risen from 10% in 2000 to 52% today.

That's only sustainable if the rest of the country continues to expand faster than the growth in those transfers, many of which are "mandatory" in the form of social security and Medicare. And while neither Presidential candidate has much of an idea of how to do that, these aren't new problems, and yet the US economy tends to keep trucking on regardless. It truly is a remarkable beast – something I'll explore further in the next post!

Have a great weekend.

Update: You can read part two, which is now open access, here.