Friday Fodder (20/24)

The federal government wants to create a big new database to protect us from ourselves; who would an autonomous vehicle choose to save, a pedestrian or its passengers; a tale of two central banks; and the UK election in one chart (it's not looking good for Rishi).

1. The social media Trojan Horse

We know that social media can cause harms, and that teenage girls as a group seem to be especially vulnerable. But many people, including teenagers, also derive benefits from social media. So I was quite concerned when I read that Prime Minister Anthony Albanese had already launched "a $6.5 million [social media] age verification trial", despite the government's Joint Select Committee on Social Media and Australian Society yet to even release its interim report.

Regardless of what that report says, it seems our politicians have already made up their minds. Albo's move was backed up by the opposition leader, Peter Dutton, who "strongly supports" age verification for social media, along with the Premiers of NSW, VIC and QLD. SA's Premier, Peter Malinauskas, has already sought legal advice as to whether he can just go ahead and ban social media for kids.

The desire for age limits isn't new; politicians have, in the past, called for restrictions and bans on everything from comic books to Pac-Man. But we must be very careful not to misread the data and impose policy that causes even greater harms.

I've gone over the tenuous social media and self harm links before, but not in an Australian context. So when NSW Premier Chris Minns decided to cite some of it, I just had to fact check him:

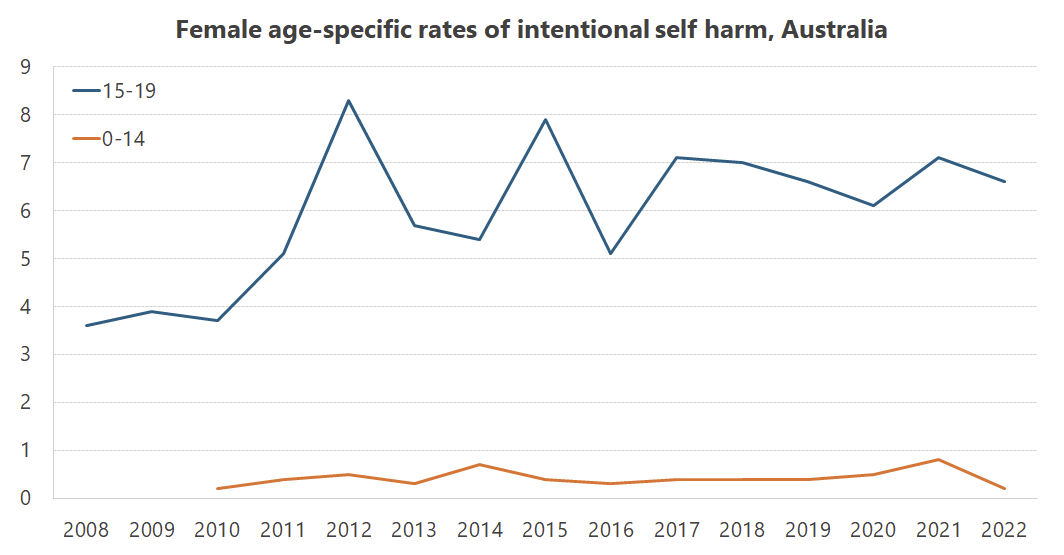

"The statistics are really troubling, so from 2008 to 2022 rates of self harm doubled for girls between the ages of 15 and 19. And they tripled for children under the age of 14. And that almost to the day coincided with the prevalence of social media."

There are two problems with that statement, both of which indicate either that Minns is being deliberately misleading, or is innumerate.

Problem one: correlation is not causation. There may be other reasons for the rise in self harm among young girls, and those need to be tested before we can draw conclusions about causation. It turns out the internet might also make women aged 15–24 less happy. Maybe that's a cause; should we age restrict that? Why is self harm among girls aged 15-19 falling in Denmark, the country with the world's highest smartphone penetration in 2017? What are the parents doing? The schools?

These, and many possible confounders, need to be explored. As our stats bureau cautions:

"Circumstances relating to a suicide are complex and multifaceted. Often, it is the combination of multiple factors rather than a single reason that contribute to a person dying by suicide. Risk factors should not be considered in isolation."

Problem two: base years and percentages can be misleading. Minns is correct that the rate of self harm roughly doubled between 2008 and 2022 for girls aged 15-19. But it has also fallen 20% since its peak in 2012, and Instagram didn't even exist until October 2010.

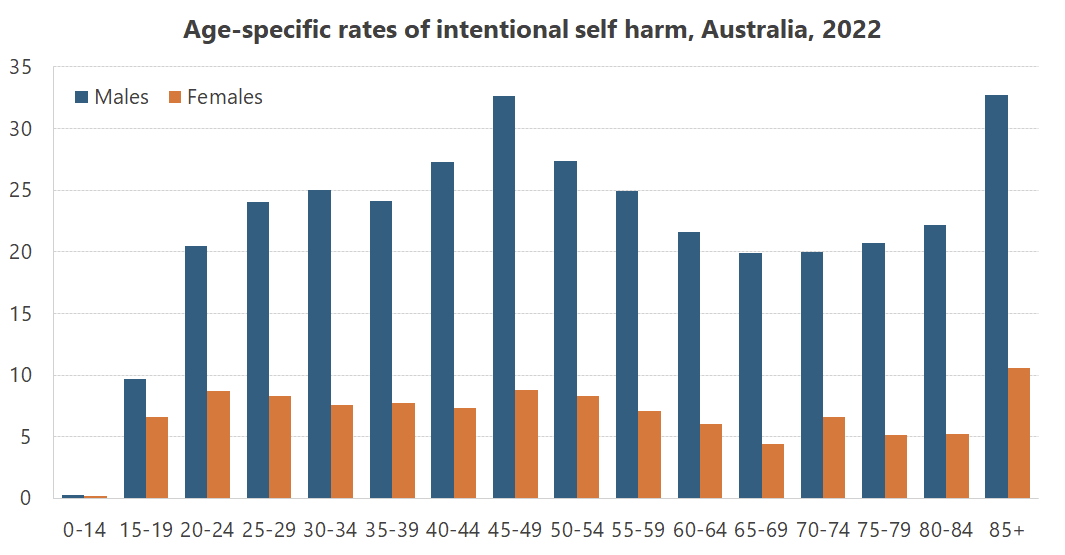

Moreover, the rate is still incredibly low; Australian girls aged 15-19 are far less likely to commit self harm than males of any age over 14.

But no one is challenging our politicians on their misreading of the data; the mainstream media has jumped right on board the censorship wagon, with the Daily Telegraph going as far as running an entire campaign against social media called Let Them Be Kids. They know which side their bread is buttered and have stopped even pretending to hold to account the government when it comes to social media.

But seriously, we should be extremely wary when both political parties and the media get together – it's always in the name of "the children", isn't it? – to propose solutions to supposed problems that could have wide-ranging consequences. In this case, social media age limits may be nothing but a Trojan Horse for a new, centralised online verification database containing all of our details.

If that's the case, then what's next; a China-style social credit system?

And for what? To protect people from the harms of social media, when the actual science generally shows that the causal effect of social media on mental health is "statistically no different than zero"? If the government really cared about saving lives, there are ways of doing it that don't involve eroding what little privacy and freedom of expression we have left in this country.

2. Should it stay, or swerve?

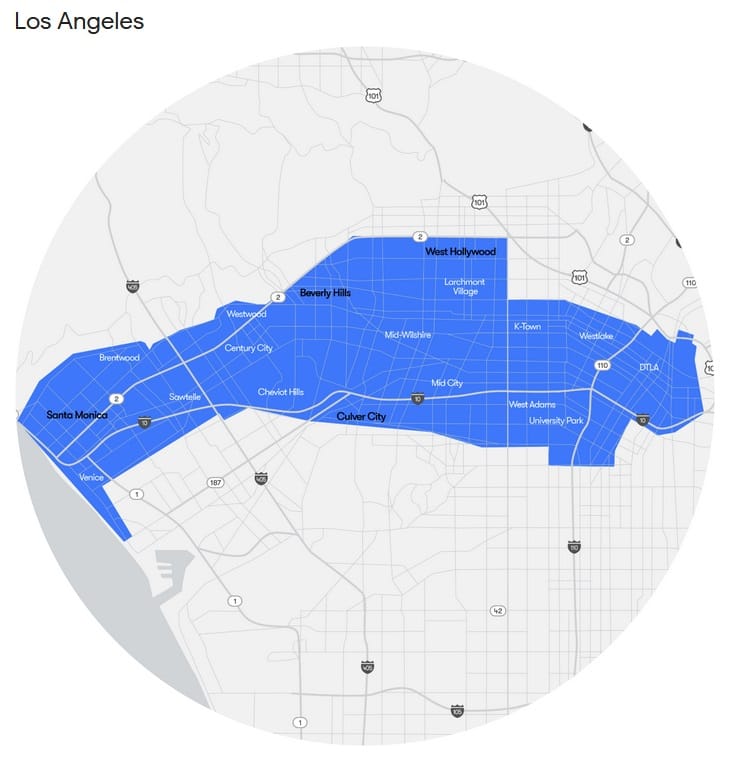

Autonomous (self-driving) cars could one day be a reality in a city near you. Yeah, yeah, Elon Musk has promised that they're right around the corner for nearly a decade, yet here I am still driving my own car. But the race for the technology never stopped, and there's no reason why it ever will until we get there: in fact, Tesla will unveil a purpose-built robotaxi on 8 August, and Google's Waymo has already been operating full self-driving taxis in three US cities since 2021, provided you stay within its 'operating zones':

The reason for the zones is because the only way for a Waymo car to drive safely is if Google spends considerable time and effort mapping the area first:

"To create a map for a new location, our team starts by manually driving our sensor equipped vehicles down each street, so our custom lidar can paint a 3D picture of the new environment. This data is then processed to form a map that provides meaningful context for the Waymo Driver, such as speed limits and where lane lines and traffic signals are located. Then finally, before a map gets shared with the rest of the self-driving fleet, we test and verify it so it’s ready to be deployed."

There are obvious scaling issues with such a model but I guess given enough time, resources, and technological advances, Google could plausibly map most of the world's cities (roads evolve so there's a need to constantly 'rebuild' the maps, so it's only likely to be economical in dense areas like cities).

Anyway, IF we ever get fully autonomous cars – notice the big IF – there are other, less technological questions that still need to be answered. For example, if a pedestrian jumps out in front of the vehicle, whose life should the AI value more: the pedestrian's, or the vehicle occupant's? A recent paper in Health Economics provided some insights:

"[W]e find that, depending on the treatment, a number of two to six passengers needs to be saved in order for the first pedestrian to be sacrificed. In the CONTROL treatment, for example, the average respondent prefers the car to continue forward when there is one pedestrian on the road, unless the car seats about four passengers or more. This means that with three passengers, the car will continue forward and save the pedestrian. Adding a fourth passenger, however, changes the preference to 'swerve', while adding a second pedestrian would change the decision back to 'continue forward'."

Food for thought if you ever find yourself in an autonomous vehicle (travel with friends?).

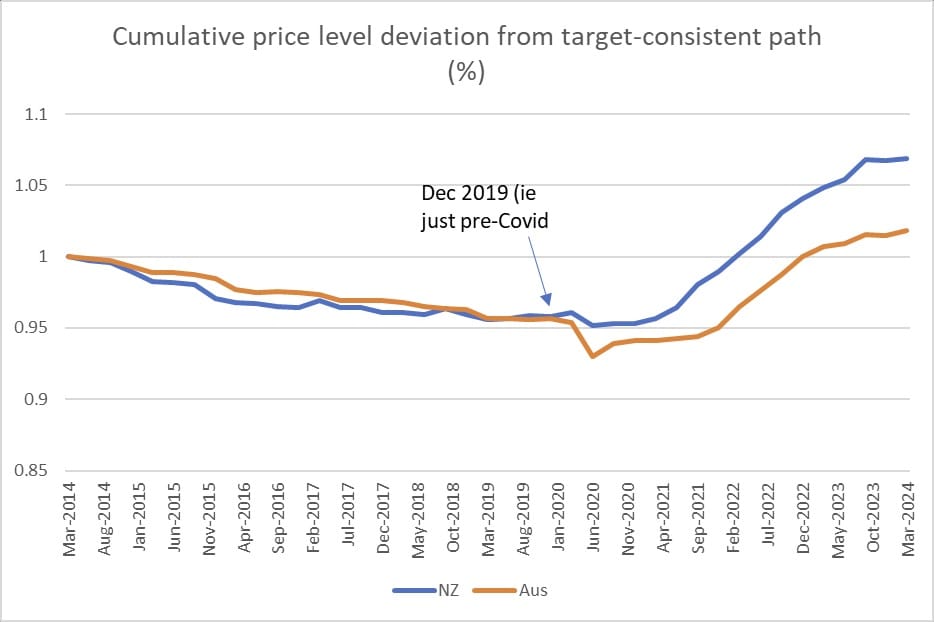

3. Two central banks

Kiwi economist Michael Reddell wrote an interesting post this week that I thought was worth sharing because of how it related to our own Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA).

It turns out that both central banks – that is, the RBA and the Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ) – undershot their respective inflation targets in the ~six years leading up to the pandemic. As we all know, they then overshot them in a big way following the pandemic, to the point that all those years of mistakes have now been wiped out – and some:

People don't mind all that much when a central bank undershoots its target; it just means they lose a little bit less of their incomes to bracket creep or savings to inflation than was intended. But when inflation overshoots the target people do care. Although, as Reddell ponders, central banks have still avoided much of the public's wrath:

"It remains somewhat remarkable how little serious accountability there has been for serious Reserve Bank policy errors, for which now pretty much everyone (except them) is paying the price, in one form or another."

Meanwhile, we have nearly a dozen ongoing inquiries into our supermarkets led by muppets like Greens senator Nick McKim who are "more interested in creating gotcha headlines than producing anything that might actually improve outcomes". Go figure.

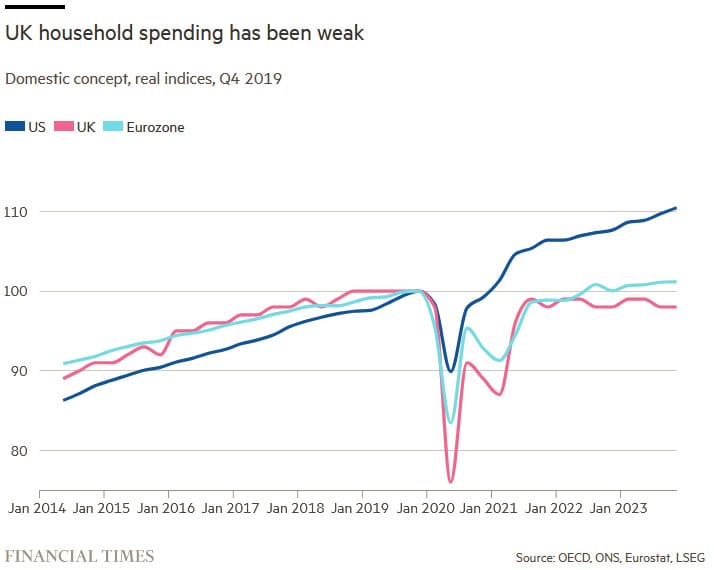

4. The UK election in one chart

UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak has called an election for 4 July and as far as the bookies are concerned, he looks set to lose. In fact, "we'd be staggered if the outcome isn't a Labour Majority".

That's perhaps unsurprising, considering that UK households have gone backwards since 2019:

It doesn't matter what caused the fall in living standards. Households are feeling it, and if your party has been in power for the past fourteen years, you're getting the blame and the flick.

5. If you missed it, from Aussienomics

Cutting migration won't solve the housing crisis – Peter Dutton claims cutting migration will free up over 100,000 homes and fix Australia's housing crisis. But his numbers don't add up and the impact will likely be minimal. Dutton's playing to anti-migration sentiment rather than addressing the real policy drivers behind unaffordable housing.

Why real wages had to fall – Real wages in Australia have stagnated because the pandemic made us all poorer; a lack of wage growth just reflects that reality. If we push wages further above productivity, we risk disemployment, a wage-price spiral, and even a painful recession.

Have a great weekend.