False prophets, forward guidance, and failed lessons

The RBA's conflicting statements on uncertainty and accountability expose a dangerous pattern of misguided forward guidance and unlearned lessons, threatening its credibility and effectiveness in controlling inflation.

Last week, the Reserve Bank of Australia's (RBA) deputy governor and governor made what I can only describe as deliberately bold and somewhat contradictory statements about accountability, uncertainty and what it all means for monetary policy. I'm not sure how they missed the contradiction, and it worries me that they may have learned very little from the experience of the past few years.

Anyway, first up was deputy governor Andrew Hauser, who used his second speech in eight months on the job to rip into the media with a provocatively titled piece called Beware False Prophets:

"Of course, eye-catching language sells newspapers, secures clients and draws crowds to the soapbox. But when the stakes are so high, claiming supreme confidence or certainty over what is an intrinsically uncertain and ambiguous outlook is a dangerous game. At best, it needlessly weaponises an important but difficult process of discovery. At worst, it risks driving poor analysis and decision-making that could harm the welfare of all Australians. It is right to want to be confident that the central bank will bring inflation back to target and maintain full employment: that is the RBA's mandate, and we should be held to account for it. But the policy strategy required to deliver that outcome, and the economic judgements that inform it, simply cannot be stated with anything like the same degree of certainty. Those pretending otherwise are false prophets."

I generally agree with that sentiment, although it's a bit hypocritical; the Review of the RBA found that its staff demonstrated "insularity, arrogance, and over-confidence", and the RBA has on many occasions engaged in precisely the behaviour that Hauser accused others of doing. Recall that former governor Philip Lowe claimed, at least three times over the course of 2021, that he was going to hold firm on rates until 2024 – only to start hiking in May 2022.

A little introspection would have been nice.

But back to the speech, which brings into question a lot of what the RBA itself says and does publicly. For example, it publishes regular forecasts, the most recent of which goes out to the end of 2026. But why bother? Governor Michelle Bullock basically says they're rubbish, with "substantial uncertainty around them, more so the further out the forecasts are".

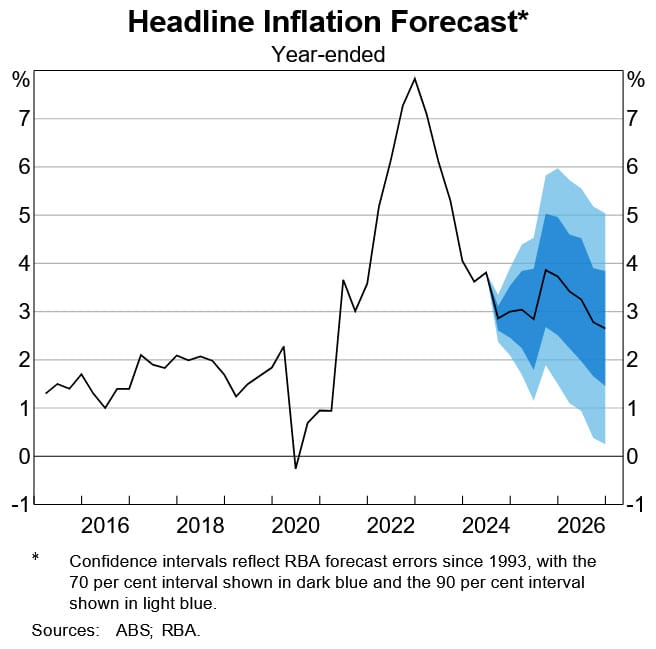

Unlike elected governments, the RBA doesn't need to cost election commitments over the forward estimates. And central banks struggle to foresee three months into the future, let alone nearly three years. It's why charts like this from its recent outlook have such huge errors bands in both directions:

The RBA also talks too much in its attempt to manage expectations – what it calls "forward guidance", or the attempt to influence financial conditions in the present by speculating about the future. Philip Lowe learned the hard way why that's such as bad idea, but it didn't get a mention in Hauser's speech.

A warning across the ditch

If the RBA needed another example of how forward guidance can be dangerous, the Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ) was just burned hard by that strategy, and has suffered a serious hit to its credibility as a result:

"Infometrics chief executive Brad Olsen previously said 'heads should roll' if a cut happened this week, given the economy had progressed much as the Reserve Bank was expecting it to when it forecast no cut until 2025 [in May].

In its statement, the bank's only acknowledgement of its changed view was a reference to 'high-frequency indicators' pointing to material weakening in activity.

'The bank seems to have just ignored what it did in May and hope the rest of us forget – we won't,' Olsen said."

Should the RBNZ have cut? Absolutely; New Zealand is in its third recession in as many years, and inflation has come down significantly. The error wasn't in last week's decision to cut but in May's forecast, which "badly misread how the economy was unfolding".

There really was no excuse; as former RBNZ economist Michael Reddell noted, the central bank was so confident in its position that it ignored the evidence and pigheadedly stuck with what it thought its models were telling it (sound familiar?):

"There has been no nasty external shock in that time (global financial crisis, pandemic, collapse in commodity prices etc) but we've gone from a 'hawkish hold' (best guess, no easing until this time next year, and possibly some tightening late this year) to not only an OCR cut now, but a really large (at peak 130 basis points) change in the projected forward track for the OCR. I can't recall another change that large that quickly, in the absence of a major external shock, in the 27 years since the Bank started publishing these forward tracks."

Central banks need to ditch the forward guidance and other attempts at managing expectations. Maintain credibility by setting monetary policy appropriately, and the expectations will take care of themselves.

The RBA should admit its mistakes

A good way to restore credibility and convince people that your culture has moved on from one of "insularity, arrogance, and over-confidence" is to express humility and fess up to your mistakes. Hauser's speech stopped short of doing that, probably because one of them cost taxpayers $50 billion and has yet to receive any media attention. But at least he said they're learning:

"By learning continuously – from our own forecast errors, from diverse quantitative models, from corporate liaison and other qualitative intelligence-gathering, from experience in other countries, and from internal and external challenge, including scenarios and 'what-ifs'. By communicating clearly and openly about what we don't know, as well as what we do. And by adopting policy strategies that reflect risks to the outlook, as well as the central case."

The thing is, it's one thing to say you've changed, but the proof is in what you do. So has the RBA really changed? Lowe's replacement as governor, Michelle Bullock, started well when back in March she did exactly what Hauser professed, telling journalists that "I won't be giving forward guidance... we're not ruling anything in and we're not ruling anything out".

Great: everything should be on the table, at every meeting! You just look foolish if you rule out a rate change months from now because your models tell you it's impossible for inflation to be that high/low. The fact is macro models just aren't very good: in 2020, they told the RBA that inflation would be below-target until December 2024. Then in 2021, they told the RBA not to worry because even though there's inflation, it's all supply-induced so it will be transitory. Only in 2022 when the alarm bells started to flash – at a time when most other central banks were already well into their tightening cycles – did Lowe perform his now infamous u-turn.

Hauser's speech acknowledged these shortfalls:

"The starting point is to avoid placing too much reliance on point forecasts in the first place, and instead frame our policy decisions in terms of contingent hypotheses or judgements. Some judgements may be strongly held, and hence given a high weight in the decision; others may be very tentative and given only a low weight. Both the hypotheses, and the weights attached to them, are continuously updated through a process of learning."

The RBA doesn't have the information it needs to make a clear prediction about six weeks in the future, let alone six months. Hauser is absolutely correct when he concludes that the answer the RBA should give when asked about the future cash rate is "that we simply do not know".

Unfortunately, recent events have shown that's not how the RBA works in practice.

Round and round we go

Just five months after saying "I won't be giving forward guidance", governor Bullock couldn't help herself, telling eager journalists keen for a headline that rates would be going nowhere until at least "the end of the year":

"I think the board's feeling is that [in] the near term — by the end of the year, in the next six months — that [a rate cut] doesn't align given what the board knows at the moment and given what the forecasts are."

Bullock then repeated that to the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Economics last week, saying that it's "premature to be thinking about rate cuts".