eSafety and the market for ideas

Australia's eSafety commissioner has been given the impossible task of censoring "harmful" online content - globally. Instead of a censorship tzar of debatable value, a better approach might be to focus resources on promoting critical thinking and demand-side interventions to reduce harmful content.

I don't often venture into the realm of social issues but today I'm making an exception because the ongoing controversy and legal stoush between everyone's favourite eccentric billionaire, Elon Musk, and the Australian government is just too interesting not to.

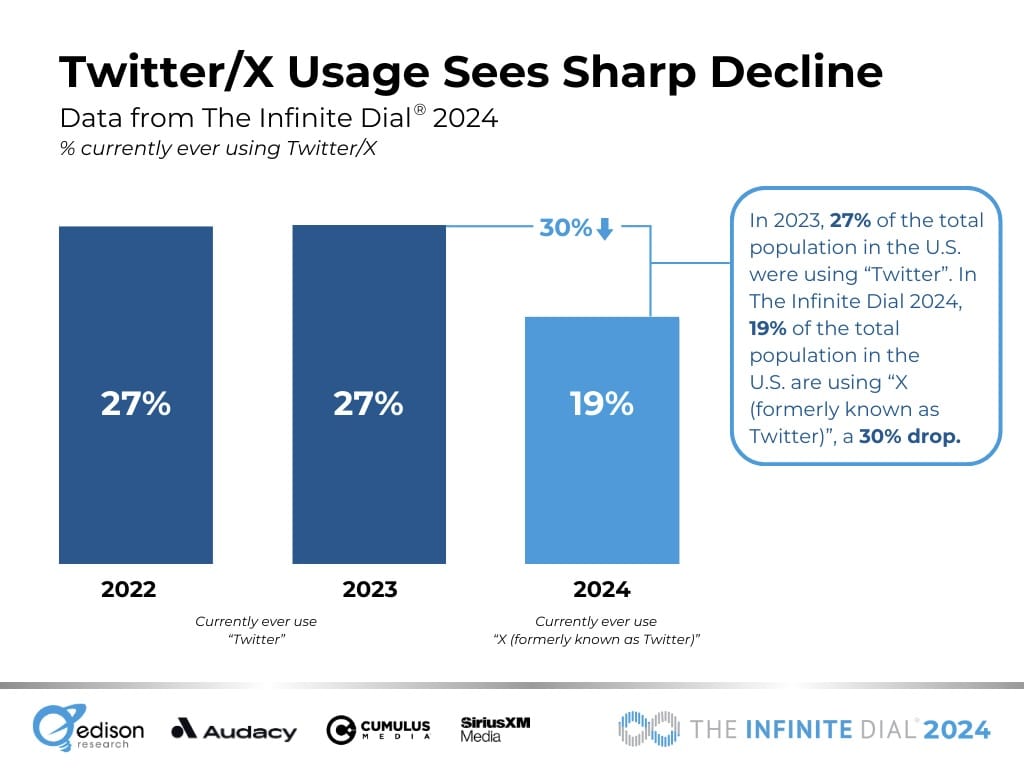

For those out of the loop, the dispute centres around whether or not Musk, the proud new owner of $44 billion social media network formerly known as Twitter (now X) – now worth somewhere in the vicinity of $12.5 billion – should have to comply with an order issued by Australia's eSafety Commission to remove a video of a stabbing at Wakeley church in New South Wales:

"The eSafety commissioner last week asked X to take down footage of the recent attack on Bishop Mar Mari Emmanuel, due to its graphic content.

On Monday, the federal court ordered Elon Musk's X to hide posts containing videos of the Sydney church stabbing from users globally. The Australian federal police told the court of fears the video could be used to encourage people to join a terrorist organisation or undertake a terrorist act.

On Wednesday, the court extended the interim injunction, ordering the posts be hidden from view until 5pm on 10 May 2024, ahead of another hearing."

The issue isn't so much that the eSafety commissioner – former Twitter employee Julie Grant – asked Musk to remove the video in Australia; it's that she asked him to purge it everywhere. In fact, Musk had no problem geoblocking the posts Down Under and did so almost immediately; his objection is that "governments should not be able to censor what citizens of other countries see online, and that regulators should stay within the boundaries of the law" [emphasis mine].

Now to me, my first instinct is to side with Musk – this seems like just a wee bit of an overreach of authority. As I dug deeper, it became very clear that the not only does the eSafety Commission have no jurisdiction in other countries, but it's debatable whether it should even exist in Australia.

The economics of ideas

The current incarnation of the eSafety Commission was the brainchild of the Morrison government, with its powers coming via the Online Safety Act (2021). The simplified task of the commissioner is "promoting online safety for Australians", which it can do with investigative powers including the ability to "obtain identity information behind anonymous online accounts", and relevant in the current debate, "order platforms to remove the 'worst of the worst' online content... no matter where it is hosted".

That sounds harmless enough – who would object to removing "child sexual abuse material and terrorist content", right?

But the whole thing got me thinking about the economics of online safety. Just because we deem something undesirable, doesn't mean that an empowered eSafety Commission is the only, or even optimal, way of combating it. In fact, depending on transaction costs, sometimes government inaction can be optimal.

A core pillar of economics is trade-offs, and there's clearly a trade-off being made here between safety and freedom of expression. And unlike the United States, where the First Amendment protects against the government "abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press", Australia has no free speech protections in its Constitution.

Alas, at federation we were clearly missing our own version of Ben Franklin, who uttered the immortal phrase of "those who would give up essential Liberty, to purchase a little temporary Safety, deserve neither Liberty nor Safety", and no doubt influenced the drafting of the First Amendment (he died less than a year after it was adopted).

Freedom of expression is, of course, vitally important to a well-functioning democracy; I don't think anyone denies that. While we have no speech protections in our Constitution, we do have "an implied freedom of political communication", a right which stems from multiple High Court decisions. In the US, political dissidents are similarly protected by the Supreme Court's Brandenburg vs Ohio ruling.

But outside of the political sphere, there's zilch; we, or our elected officials at least, are able to trade between safety and freedom. In 2021, the Morrison government decided to trade a bit of our online freedom to empower the eSafety Commission.

But economically speaking, it probably shouldn't have. Way back in 1974, Nobel laureate Ronald Coase published a fascinating journal article in the American Economic Review called The Market for Goods and the Market for Ideas. As the name implies, Coase contrasted the relatively regulated market for goods with that of the unregulated market for ideas. Coase was making the point that while intellectuals (at the time) were rigorous defenders of free speech and the market for ideas, they were not consistent in applying the "same approach for all markets when deciding on public policy". To prove his point, Coase wrote:

"[C]onsider the question of consumer ignorance which is commonly thought to be a justification for government intervention. It is hard to believe that the general public is in a better position to evaluate competing views on economic and social policy than to choose between different kinds of food. Yet there is support for regulation in the one case but not in the other.

Or consider the question of preventing fraud, for which government intervention is commonly advocated. It would be difficult to deny that newspaper articles and the speeches of politicians contain a large number of false and misleading statements – indeed, sometimes they seem to consist of little else. Government action to control false and misleading advertising is considered highly desirable. Yet a proposal to set up a Federal Press Commission or a Federal Political Commission modelled on the Federal Trade Commission would be dismissed out of hand."

Coase was being sarcastic; surely no one would be foolish enough to try to regulate the supply of speech the way we regulate the supply of certain goods, even though the case is often at least as strong (and therefore we might want to re-evaluate how we regulate goods).

But then he never met Scott Morrison.

What about demand

Being an economist, I obviously want to look at the demand and supply of "harmful content". While Australia's approach has been almost exclusively on tackling the supply side, a new working paper from researchers at the University of Chicago looked at ways to reduce misinformation by using a "focus on enhancing critical thinking skills in an effort to alter the demand side in this market".

Their results were generally positive, with a short video enough to make people around 30% "less likely to consider fake news reliable". An unintended consequence was that people became more sceptical of all news, but the point is that demand-side intervention is possible and might be cheaper and more equitable than a fully supply-side, censorship approach.

And it's not like our government has a problem regulating the demand of potentially harmful goods. For example, plain packaging cigarettes, the alcohol 'think again' campaigns, or problem gambling advertising during sporting events. It also runs educational campaigns making sure we don't get too much sun, and tells us to use less water. The federal government even has its own Behavioural Economics Team, and while it's not clear what they do, exactly, it clearly shows that the government is more than happy to "nudge" our demand in certain directions.

Perhaps, instead of playing a futile long-term game of Wack-a-Mole by trying to crack down on the supply of "harmful content", the government should focus a bit more on encouraging people to think critically and decide for themselves what is harmful or not. A supply-only strategy is doomed to fail; once something has been filmed and uploaded to the internet, no number of take-down notices will get rid of it. If someone wants to view it, they will find a way. Sure, maybe it won't be on X. But it will still be somewhere. If it's geoblocked, better hope the kids don't figure out how to use a VPN!

Anyway, the best placed actors to tackle the supply side are generally the platforms themselves. Another of Coase's key insights was that transaction costs matter. Those costs make it impossible for all 26 million Australians to negotiate with each other about what they do or don't want to see from each other online. But that doesn't mean the government should step in and perform that impossible task; instead, platforms such as X are much better placed to balance people's conflicting interests, controlling what people see so that any externalities are resolved in a least-cost manner. The government could try to influence X's policies, but the current strategy of issuing take-down notice after take-down notice will not work in the long-run.

Incentives matter, and if enough users object to harmful content – and I would expect that to be the case in any society – X would have the choice of becoming a cesspool of paedophilia and violence, or censoring the content on its platform until it approximated something that most of its users were happy with. Only one of those options potentially ensures its survival (it's a ruthless market), and the eSafety commissioner doesn't have to lift a finger to get us there.

But would Coasean bargaining and a bit of demand-side nudging from government get rid of all falsehoods and all harmful content on social media? Absolutely not. Once again, Coase observed that "the public is commonly more interested in the struggle between truth and falsehood than it is in the truth itself". People tend to be more engaged by controversy and debate about an issue, than they are in the truth or accuracy of the information being debated.

I'd love to see a cost benefit analysis

But having falsehoods existing on a social media platform is still not enough of a rationale to justify the powers that our eSafety commissioner possesses. In addition to the concerns about those powers, there are also several potential unintended consequences to consider:

- As sole determiner of what is "true" or "acceptable", the commissioner may end up suppressing minority views or unpopular opinions that may actually be true. Remember the pandemic, when the government told us all that masks were useless? Then that they were essential? Then that the virus was spread only by droplets, only for its own quarantine facilities to break down because, whoops, it actually spread via aerosol?

- It may incentivise rent-seeking or regulatory capture, where individuals or groups seek to influence the commissioner's decisions or focus.

- The threat of regulatory action may cause people to self-censor, leading to a reduction in the overall quantity and diversity of speech.

- It may drive competitors out of the market for ideas, particularly those that specialise in provocative or controversial content (satire appears to be permitted, but for how long?).

- People may be less likely to experiment with new formats, styles, or topics that could be deemed "offensive" or "harmful".

- Barriers to entry for new competitors will be higher, particularly startups that lack the resources to comply with the rules, reducing innovation and protecting incumbents.

- What if there were to be an "unsafe" video that exposed something much greater? What if we had our own George Floyd moment, but the eSafety commissioner censored it in the name of "promoting online safety for Australians"? What might that cost our society?

On the first point, I found it somewhat ironic that in supporting the eSafety commissioner's decision, Prime Minister Albanese said:

"This isn't about freedom of expression, this is about the dangerous implications that can occur when things that are simply not true, that everyone knows is not true, are replicated and weaponised in order to cause division and in this case, to promote negative statements and potentially to just inflame what was a very difficult situation. And social media has a social responsibility."

But the events in the video being debated happened. Bishop Emmanuel, the man who was stabbed, even wants the video to remain accessible because "it would be of great concern if people use the attack on me to serve their own political interests to control free speech".

It's a valid fear; independent senator Jacqui Lambie went as far as to call for Musk to be jailed, for goodness sake. Before any more speech-suppressing legislation is passed, I would love to see a cost benefit analysis of the existing laws, especially given how quickly they've proliferated over the past decade. History has shown that government regulation of the market for ideas often leads to unintended consequences and stifles innovation, yet the Australian government's answer to every perceived problem in that space has been to whack yet another layer of regulation on top.

Australia is not free (speech) country

It saddens me that our mainstream media has seemingly, in almost complete unison, taken the government's side on this issue. As has the opposition, although at least Dutton has acknowledged Australia's limited authority outside of this country. The whole thing reminds me of that jarring scene from Star Wars, when Padmé Amidala remarks:

"So this is how liberty dies. With thunderous applause."

Indeed, the mainstream media has been quite supportive of the eSafety Commission; but then they've been quite hostile to social media for many years. They're hostile because, like any good oligopolist, they had a good thing going until social media came along. While their angst was entirely misplaced, that didn't stop them getting in bed with government to pass the news media bargaining code – a textbook example of rent seeking.

However, it wouldn't have surprised Coase that the media, which depends on a certain amount of freedom of expression for its very existence, would sell out; indeed, he predicted that there will inevitably be "cases in which groups of practitioners in the market for ideas have supported government regulation and the restriction of competition when it would increase their incomes, just as we find similar behaviour in the market for goods".

But it's not hard, with only minor examination, to see the slippery slope on which the media's support rests. Today it's videos on X; tomorrow it could be the media's own reporting. The day after that, perhaps news articles on anything other than silly kittens needs to be cleared by a politician's office or the eSafety commissioner prior to publication. Just to be sure that it contains the facts and the facts only, of course.

Our slide toward censorship has been happening for at least a decade. The University of Queensland's Katharine Gelber tracked the descent in a 2017 journal article, warning that:

"This evidence tells a consistent tale of governments' extension of their regulatory powers at both federal and state levels, in a manner that restricts free speech... the types of speech restricted in the laws discussed above [during the period 2011–2016] are far more broad and affect a far greater range of speech than that which should be considered legitimately regulable. They prohibit discourse about government acting illegally, speech with only tangential and marginal connections with the risks of directly and intentionally inciting others to commit terrorist acts, the disclosure of harmful practices by government in controversial policy areas, and peaceful protest...

It is only possible to conclude that most of these restrictions are harmful to opportunities for democratic practice and legitimacy in Australia."

That was published prior to both the eSafety Commission's empowerment in 2021 and the potentially much more dangerous Combating Misinformation and Disinformation Bill, which despite being shelved late last year looks to have found renewed bipartisan support.

We're not just on the slippery slope to China; we're quite far down it. Restricting speech and content has become normalised within both state and federal governments, not to mention by the media, with the door very much ajar for an even bigger and more abusive censorship regime in the near future.

But at least we'll be safe... right?