Death by a thousand links

Facebook leaving Australia shows that the media bargaining code backfired. The government misdiagnosed the problem and harmed consumers while benefiting the big media companies. It's time to cut our losses, accept that the code was a mistake, and focus on real solutions to support local media.

If you somehow missed it (the media were all up in arms), late last week Facebook's owner, Meta, announced that in early April it "will deprecate Facebook News, a dedicated tab for news content, in the United States and Australia".

The decision is a huge slap in the face to the Australian government, which in 2021 passed legislation with bipartisan support to enable the news media bargaining code (henceforth 'code'). Meta protested at the time – even threatening to withdraw from Australia – before it (and Google) eventually caved and struck deals with media companies worth around $200 million annually, leading then-ACCC chair Rod Sims to call it "one of the most successful public policy interventions I've seen".

The infamous media bargaining code

The TL;DR of the code is that it gave the Australian Treasurer of the day the power to "designate" a digital platform – Meta (Facebook) or Alphabet (Google) – at which point the companies involved would face compulsory arbitration to be determined by a panel appointed by the government's Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA). But according to Sims, that was all just part of the shakedown:

"We never wanted to go to arbitration, we just wanted the threat. What happened in the Code was that the threat of arbitration was replaced by the threat of designation. What we learnt was that Facebook and Google just did not want to get designated."

True. But it turns out they also don't like paying media companies for the privilege of linking to their articles, given that's not how the internet works. That should have been obvious from the start: if Facebook and Google were truly exploiting their bargaining power over Australian media companies, those companies could always have stopped them indexing their news at virtually zero cost. But they didn't, because media companies need their articles on Google and Facebook more than Google and Facebook need their news.

And so it was that after initially paying the shakedown fee, Facebook is going to stop serving news to the Australian market when those initial deals expire; and with no "News" product, Meta will no longer have to pay Australian media organisations for the privilege of linking to their articles:

"[W]e will not enter into new commercial deals for traditional news content in these countries and will not offer new Facebook products specifically for news publishers in the future."

Needless to say, the Australian government was not thrilled. Prime Minister Anthony Albanese said it was "not the Australian way":

"It is absolutely critical that the media is able to function and be properly funded. We will consider what options we have available and we will talk to the media companies as well. The idea that one company can profit from others' investment, not just investment in capital but investment in people, investment in journalism is unfair. That's not the Australian way."

Assistant Treasurer Stephen Jones said Meta's actions were "a dereliction of its commitment to the sustainability of Australian news media", and that:

"The Australian government is committed to the news media bargaining code and is seeking advice from Treasury and the ACCC (Australian Competition and Consumer Commission) on next steps. We will now work through all available options under the news media bargaining code."

Now, whether Meta and Alphabet pay enough tax in Australia given their use of transfer pricing via countries such as Ireland is a legitimate question. But the code does not address that, and if you wanted to help Australia's media companies then there are much better ways to achieve that than upending an entire market at potentially great cost to consumers.

A tax and a subsidy dressed up as competition reform

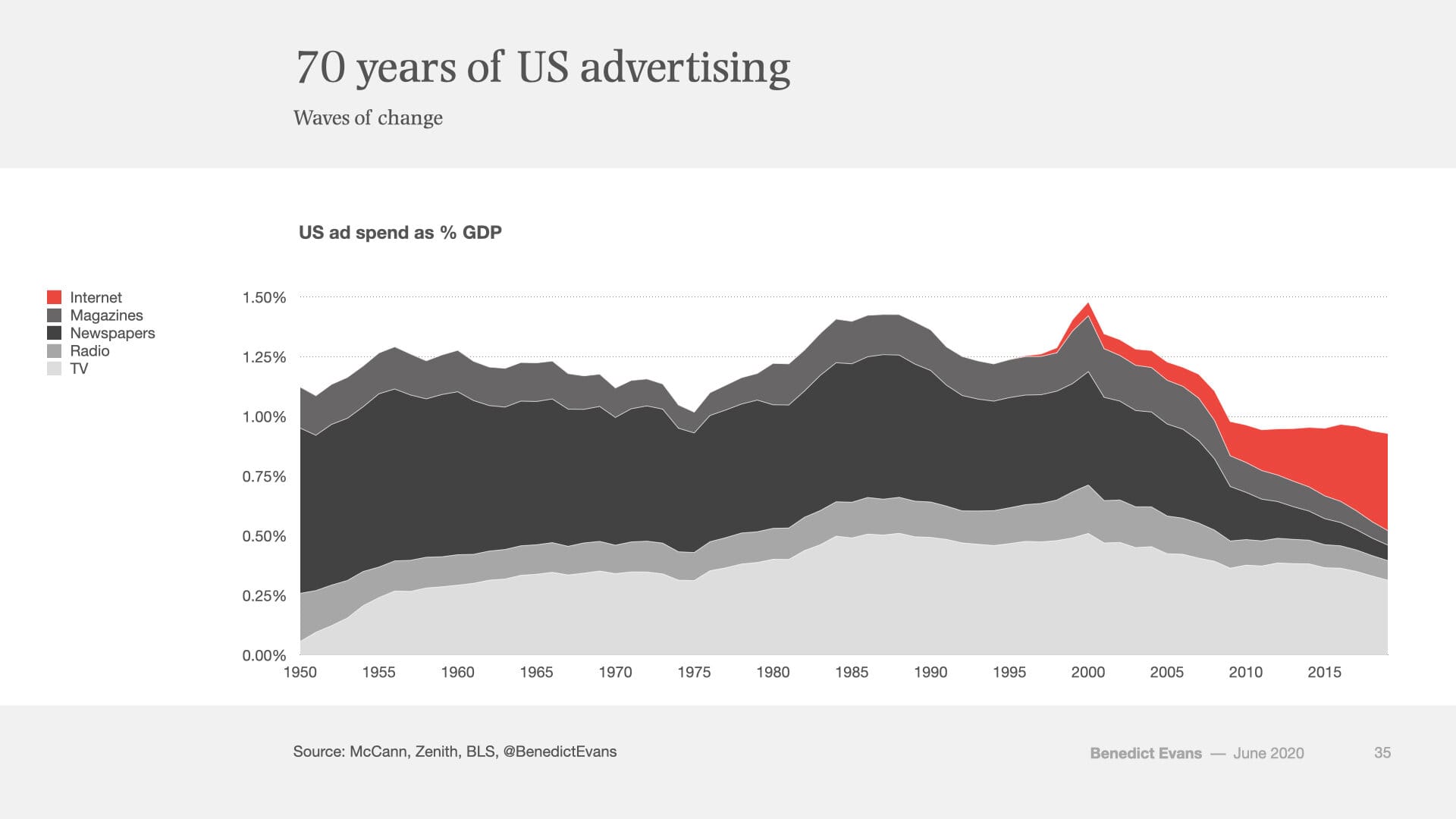

To understand why Frydenberg and the Liberal Party, with the support of the Labor Party, implemented this tax in the first place we need only look at advertising revenue data. Adverts were traditionally the lifeblood of media outlets, but with the rise of the internet, new forms of media started to pull eyeballs and adverting dollars away from news media:

You might think, as Rod Sims and many of Australia's politicians did, that it's Google and Facebook eating up that revenue. For instance, Michael Miller, Executive Chairman of News Corp Australasia, made this claim after Meta announced its departure:

"Publications, especially longstanding mastheads serving regional Australians, have been challenged as Facebook has hoovered up the valuable advertising dollars that once supported them.

The Australian government must protect these smaller communities who will be the real victims of Meta's decision to not compensate publications for the local news they produce."

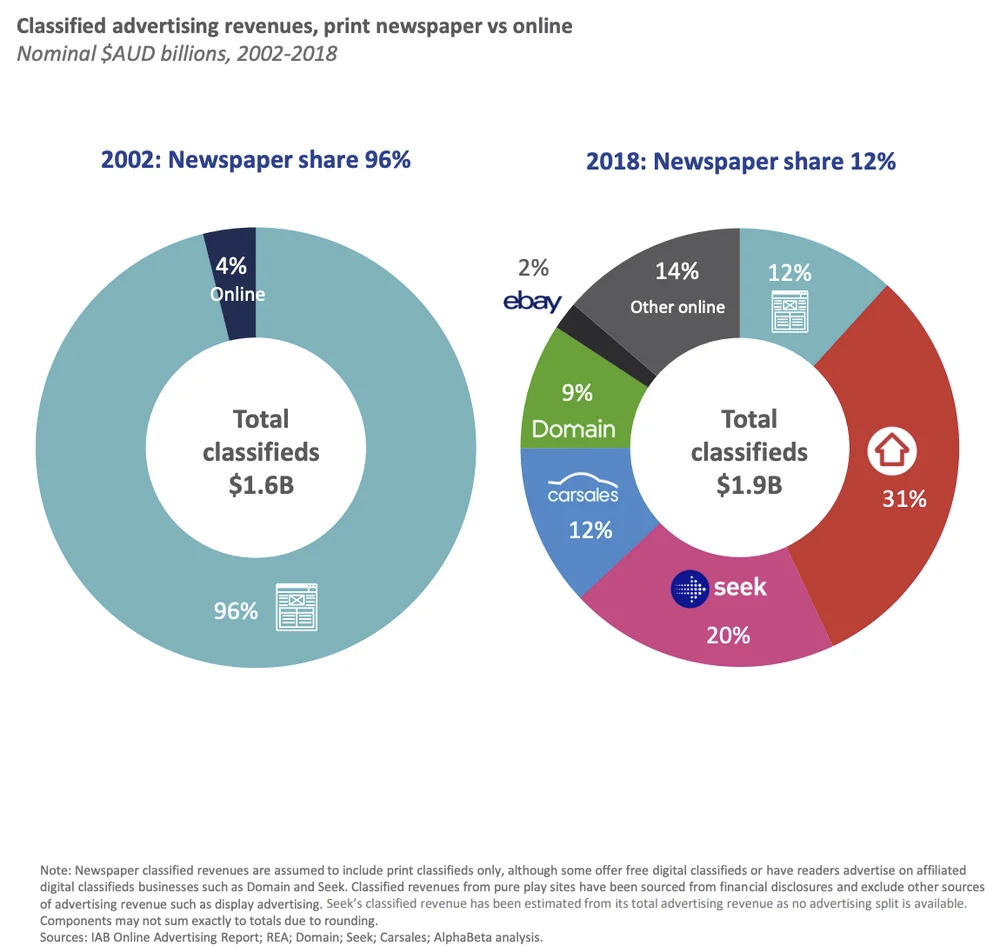

But Facebook and Google generate very little revenue from news advertising; the real cannibalisation of news media's revenue came from the demise of classified advertising. And the cause of that was the internet itself, not Facebook or Google: a plethora of websites popped up that allowed people to bypass newspapers and list products and services for sale, at lower cost, such as on Craigslist (Gumtree in Australia).

Even if the Australian government had correctly identified the likes of Gumtree, rather than Facebook and Google, as the cause of media's woes, change was inevitable:

"The reality is that the decline of print advertising rates and the resulting effect on newspaper revenue would likely have occurred with or without Craigslist [Gumtree], driven by the explosion of webpages and ad providers and the advertising industry's increasing desire to focus on digital markets, not print-based ones. And those factors were arguably compounded by the newspaper industry's focus on dumping commodity news content onto the web without approaching it as a separate market, the way web-native providers did."

In effect, the entire advertising market structure shifted and media companies failed to adapt in time, causing them to lose market share and revenue. The demise of Australia's media companies correlated with the rise of Facebook and Google, making them easy targets, but they are not the cause.

Facebook and Google grew by serving an entirely different market:

"[I]f you talk to people at both Google and Facebook and in the agency world, you'll hear that a lot of the money spent on Google and Facebook is money that was never spent on traditional advertising - it's coming from SMEs and local businesses that might have spent in classified at most but probably wouldn't have done even that. $60bn of consumer spending went through Shopify last year - it's safe to assume those vendors spent money on advertising, but how many of them would have bought an ad in a local newspaper? This has also come at much lower prices: Facebook in particular has been massively deflationary to online advertising: it offers vast quantities of relevant advertising inventory at much lower prices and much lower entry costs than you'd have needed in print, let alone TV."

By misdiagnosing the problem, our government passed legislation that will almost certainly cause consumer harm by taking away their options. The benefits – most of which have accrued to well-connected, large media companies including those owned by billionaires such as Kerry Stokes and Rupert Murdoch – will be transitory, as Meta and potentially Google decide to simply walk away.

Throw it out and start again

Treasury's 2022 review of the code gave it a thumbs up because of the "30 commercial agreements" struck between platforms and media companies, nearly half of which involved Meta. But Treasury did note some "other issues", including:

- that the Code has created resource disparities between news businesses, particularly those with and without deals, which has left the latter at a competitive disadvantage;

- that the lack of transparency about commercial agreements undermines the ability to assess whether the Code has achieved its policy objectives;

- that the Code should oblige news businesses to spend remuneration received from digital platforms on public interest journalism, or at least publicly report how they spend this remuneration; and

- that smaller news businesses face particular challenges under the Code.

These unintended (though easily anticipated) consequences should form a more significant part of Treasury's new advice to the government, especially now that one of the cash cows the code was designed to milk – the revenue from which was the sole reason for Treasury declaring it a "success to date" – has now fled the country.

In fact, I hope that the primary option offered by Treasury and the ACCC is the complete removal of the news media bargaining code. But that's no guarantee, given that the ACCC – at least when it was run by former chair Rod Sims – seemed to misunderstand what competition is when it concocted the code, claiming that there was a "bargaining imbalance that exists between digital platforms and media companies, which represents a classic market failure".

The thing is, there are lots of bargaining imbalances in the economy (markets are not perfectly competitive), and if the government prevented people from making deals except when they had equal bargaining power, then almost all trade would be forbidden. Contra Sims, there's no market failure unless there's an exploitation of a bargaining imbalance and an unfair exchange of value – say, if one firm had monopoly/monopsony power – which, ironically, is precisely the what the code sets up: it uses the government's monopoly on force to create an unfair exchange of value from Facebook and Google to large Australian media companies.

The government should revoke the code before it does any more damage. In the short run, the code could cause Google to also head for the exits, as it did in Spain and Canada after they passed similar legislation. In the long run, propping up Australia's highly concentrated group of media companies risks prolonging obsolete business models at the expense of those that leverage the internet, rather than fight it, jeopardising local media's future.

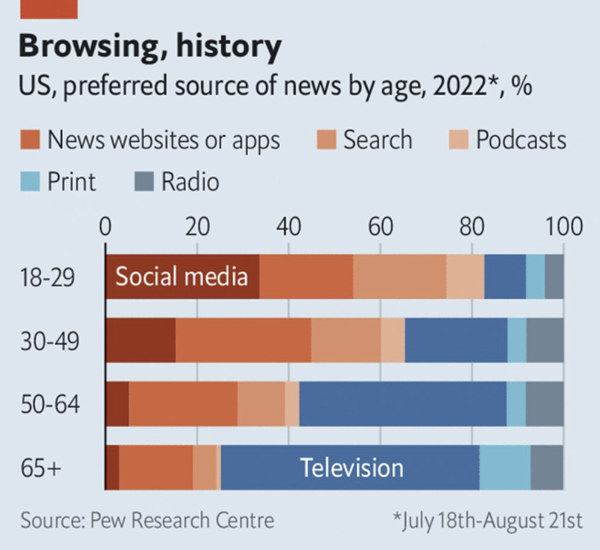

The fact of the matter is that people aren't consuming news as they once did; there's an irreversible, generational shift underway, and Australian media would be better off competing and finding ways to profit from it, rather than fighting the change itself with the help of government support.

Contrary to the claims of politicians and local media barons, having news articles show up on Google searches, Facebook timelines and X (formerly Twitter) feeds helps news media, which now makes considerable revenue from paid subscriptions: Australia boasts the "third-highest level of paid subscriptions to news sites in the world". Such referrals are especially valuable to smaller businesses such as Aussienomics, which is one of the myriad sites that are now at a "competitive disadvantage" due to the code.

It's time to cut our losses, accept that the code was a mistake, and move on. If the Albanese government truly wants to preserve local media in Australia, it should do it through direct subsidies that don't dismantle business models and unfairly discriminate against smaller, independent news media that rely on traffic from Google and Facebook News. If it's not sure from where to find those resources, it might want to look at whether the more than $1 billion a year it currently spends on propping up the ABC and SBS could be used more effectively to support local media.