Are Coles and Woolies ripping us off?

Over the past couple of years, food in Australia has become expensive. So much so that even politicians have started to (belatedly) take notice. That's usually a good sign that there's going to be some kind of policy response, once the various reviews are completed and briefing notes are prepared. I'm not sure what form it will take, or how and when it will happen, but the sheer volume of political statements made over the past couple of weeks all but guarantees something is brewing. The common thread throughout: the perceived lack of competition and pricing power in the sector, but especially for the two major supermarket chains, Coles and Woolworths.

The criticism of 'Colesworth'

The federal government has been sniffing around the supermarket sector since late last year, announcing a review into the Food and Grocery Code of Conduct back at the start of October, and earlier this week confirmed that Labor's former Competition, Trade and Small business Minister Craig Emerson will lead it (with the support of Treasury).

In December, the Senate – led by the Greens but supported by Labor – triggered an inquiry into "the price setting practices and market power of major supermarkets", with a final report due by 7 May 2024.

Since then, a number of the government's senior cabinet members have spoken up about grocery prices, all while alluding to mischief on behalf of the big supermarkets. For example, just before the New Year the Minister for the Environment and Water, Tanya Plibersek, weighed in:

"What I would say is I've got every sympathy with those farmers who are being pressured to accept very low prices from our supermarkets. It is one of the problems with having such a concentration of ownership of supermarkets in Australia, and it is something that I accept, absolutely, that farmers are pressured to take those very low prices because they don't have a lot of options when it comes to selling their produce. So, we do need to continue to work on more contestability, more competition in the Australian supermarket sector."

Earlier this week, Treasurer Jim Chalmers also fired a not-so-subtle shot at the supermarkets, reminding them of the regulatory influence he wields:

"When the price of meat and fruit and veggies comes down for supermarkets, it should come down for families as well. I'm in regular contact with the ACCC chair about these sorts of issues, and if further steps are necessary, we will obviously consider them."

Independent Senator David Pocock even asked whether supermarkets should be forced to display what they pay farmers for their goods, an idea that seemed quite popular with his followers.

The perception that we're being gouged by the supermarkets has even flowed down to state politics. Queensland's Premier, Steven Miles, wrote to the bosses of Coles, Woolworths, IGA and ALDI last week expressing his "concern about a widening gap between the prices farmers receive for their produce and the prices consumers pay at the checkout in your supermarkets".

There is no question that food prices have gone up. As a share of the 'things we spend our incomes on', food costs have risen faster than everything other than housing over the past year. People are paying more at the checkout and they're writing and calling their local members to express their displeasure – a completely valid response.

But is there any merit to the claim that higher food prices are the result of deliberate price gouging, or is something else afoot? Let's take a deeper look.

Why is food so expensive

The main reason food is so expensive is because everything is more expensive. Food just happens to be something we spend a lot of our incomes on, and we do it several times a week. When prices go up, we tend to notice.

That's important, but it could also lead politicians – who are almost always in election mode, so need to be seen taking their constituents' complaints seriously – astray. And the most vocal group appears to be farmers, who have noticed that while the prices for their goods have fallen or stopped rising as much, grocery prices haven't immediately followed:

Ross Marsolino from Natural Earth Produce, a zucchini, tomato and eggplant producer in Victoria's Goulburn Valley, told Sunrise this morning the situation was "getting worse". "It's not getting any better," he said. "They are earning too much money, where is that gap going? Who is making the difference? The supermarkets... Why are you making so much, why is there any need to make so much profit?"

Trevor Cross, who has a farm in Queensland and was forced to "dump 2,000 tonnes of pumpkins last year" due to low prices, wants supermarkets to "just give us some money to do what we do so we can survive, and they shouldn't be gouging the customer at the other end".

The National Farmers Federation's President, David Jochinke, echoed that sentiment with a call for Australia's consumer and competition regulator, the ACCC, to be given "some more teeth":

"They need to have more strength and more ability to actually investigate these concerns when they raised so that when we talk about the price of food, when we talk about the cost price squeeze on the average Australian and then also what is a fair price on agriculture, they can kick into gear."

There are a few problems with these claims. While I'm fully supportive of the ACCC investigating price gouging – it's important not just to have the correct rules in place, but also to properly enforce them – there is no reason at all why supermarkets should be forced to buy everything farmers want to sell, just because "we had to do all the work to grow it", as claimed by Mr Cross.

Farmers should of course be paid, provided they produce what people want at prices they're willing to pay. Supermarkets aren't avoiding pumpkins because they're looking to limit supply and gouge consumers; if there's margin to be made, they'll make it (or their competition will). The reason they're not buying all the pumpkins is because there are only so many Australians who want them, and at the margin higher cost producers are generally the ones who lose out.

There are also good reasons why falling prices for farm goods don't necessarily translate into lower grocery prices right away. Nationals leader David Littleproud this week labelled Coles and Woolworths "worst corporate citizens in this country", questioning why falling cattle prices did not fully flow through to supermarket prices. But the process of getting food from the farm to the supermarket isn't as simple as having old mate Mr Cross drop the cattle off at Coles, clip his ticket, and everything then takes care of itself. Supermarkets tend to buy goods using forward contracts to provide certainty of supply and consistency to customers, which means farm prices can take a long time to flow through to final prices. Farm prices are also just one part of the story – a recent study by the US Fed found that agricultural commodity prices have only a "weak" influence on grocery store prices, with "changes in consumer income and behaviour" mattering far more.

Supermarkets also take on a lot of risk – spoiled produce, changing consumer preferences, theft – plus have their own overheads, such as staff, the cost of constructing stores, the price of energy, supply chain logistics, and packaging. If the price of any of those inputs change by more than farm goods prices, then your groceries are probably going to stay expensive, too.

Margins haven't risen all that much

Some of the angst towards supermarkets might just be that people – even farmers – don't know much about the industry. According to a consumer survey conducted in the US last year:

"Americans believe that grocery retailers are earning a 35.2% net profit margin, 14 times higher than grocers' actual net profit margin average of 2.5%, and that food-at-home inflation is 24.3%, double the annual rate reported by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics."

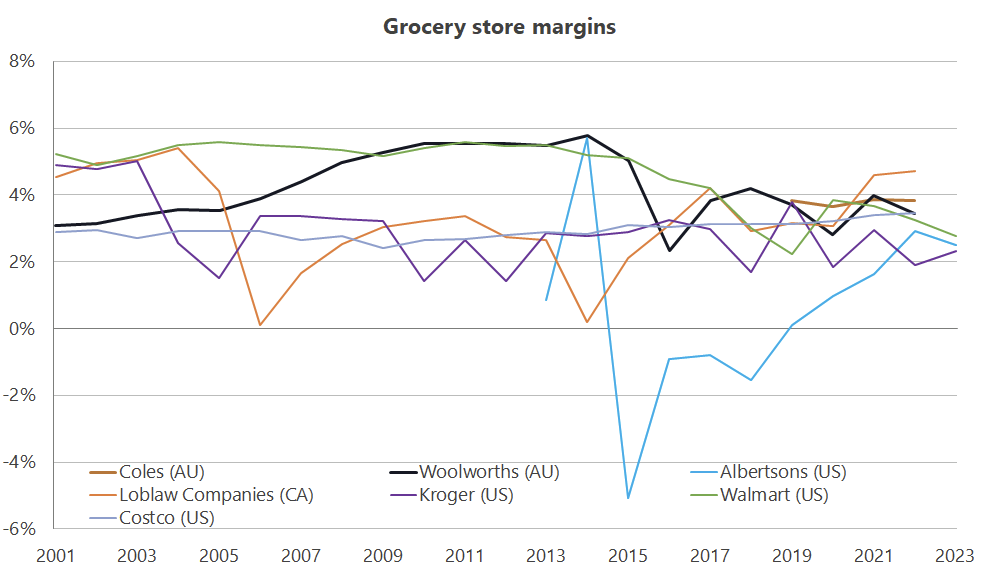

I haven't been able to find a comparable survey question in Australia (if anyone from a major bank is reading, how about adding it?) but I can compare supermarket operating margins between the two countries. A word of warning: this is a blunt indicator; for example, even if prices were unchanged margins could increase for various reasons, such as consumers switching from store-brand to private-label products, or a supermarket improving its back-end operations.

That aside, despite having a significantly more concentrated market, supermarket margins in Australia are quite small – in fact, they're similar to that of their North American peers (who, at least in the US, face a lot more competition), notwithstanding a few golden years for Woolworths from around 2009 to 2015.

That's consistent with a 2019 study by the RBA, which found that margins for both food and non-food retailers had been falling in Australia prior to the pandemic, likely due to "a reduction in firms' pricing power".

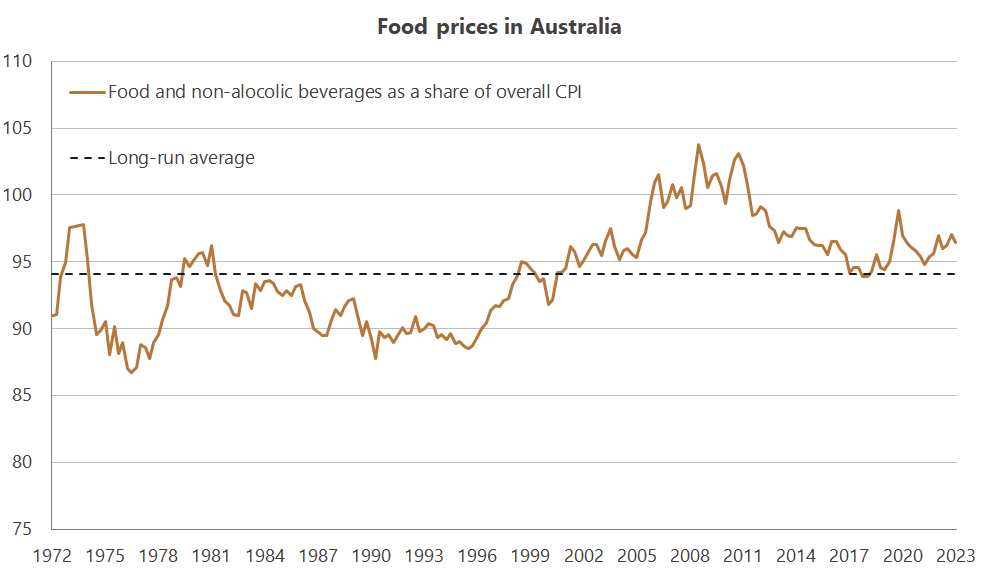

If supermarket margins are flat, and they haven't gained pricing power, then just why has food in Australia become so expensive? What's important here is context. Compared to overall prices in the economy, the relative price of 'Food and non-alcoholic beverages' hasn't increased much over the past few years. While it's slightly above the long-run average and has risen a bit in the past two years, it's still below where it has been for most of this century.

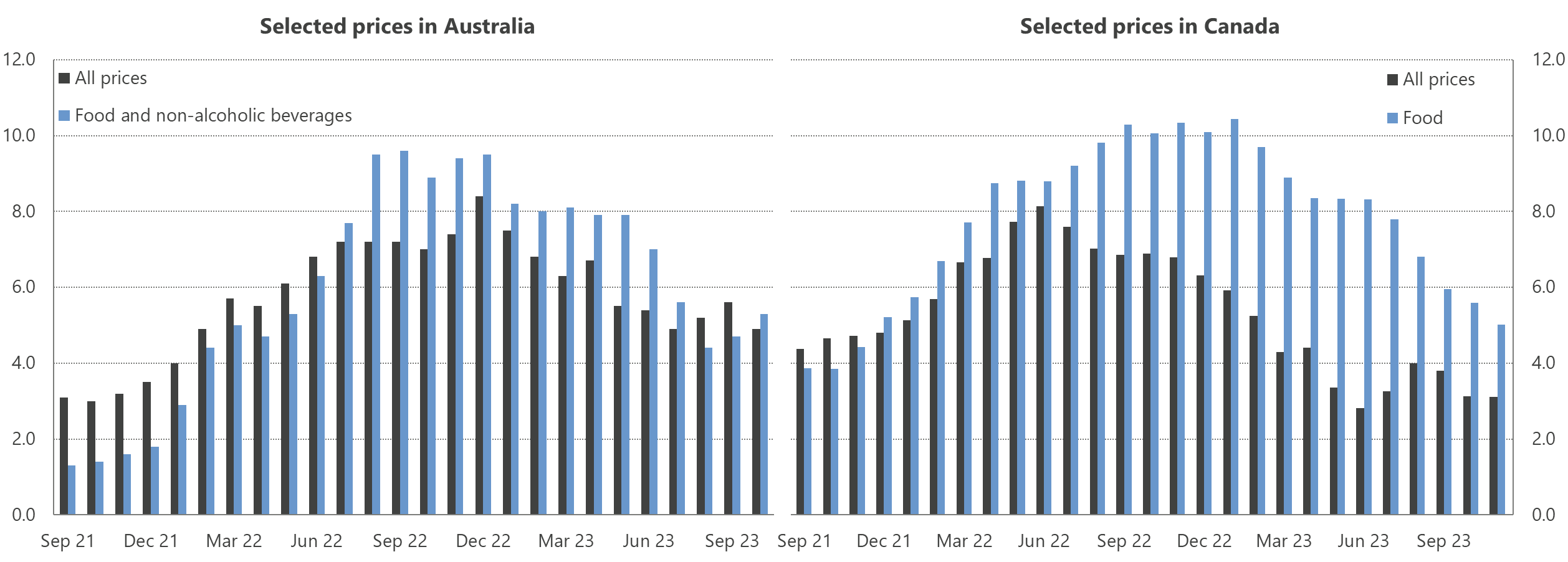

So yes, food is more expensive, but so is everything. And it could be a lot worse; we actually look reasonable when compared to our northern neighbours Canada, whose Competition Bureau recently concluded a study on its own supermarket sector. It found that a lack of competition has contributed "a modest yet meaningful amount" to higher grocery prices since around 2017. Interestingly, one of its key recommendations was to mandate pricing by a common standard (e.g., per 100g), a rule we've had in Australia since 2009.

The cause of higher food prices is higher prices

We're in a demand-driven cost-of-living crisis, and while it might sound circular, food is expensive because everything is expensive. People are just noticing higher food prices more than other things – just as they're noticing higher housing prices – because we spend more on those two items than anything else we buy. It's why the ABS gives them the highest weightings of 17.18% and 22.24%, respectively, in the CPI.

By all means, we should actively encourage competition in the supermarket sector. But a well functioning market can be competitive, even without a lot of competitors, provided it's contestable. Given Australia's relatively small, spread-out population and the benefits economies of scale can have for consumers (the cost advantages from being big), that last 'C' – contestable – should be the focus of any government inquiry.

Why I'm cautiously optimistic

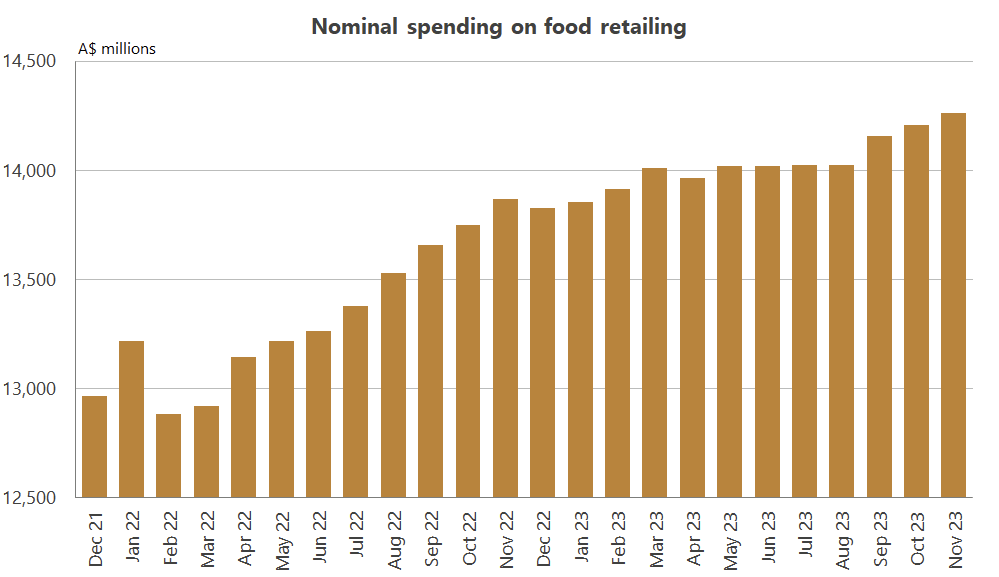

The supermarket game isn't for the faint of heart; it's a low margin business, relying on volume to achieve returns for investors. They're making record nominal profits because in an inflationary environment, even with relatively flat margins, that should be inevitable; if they weren't setting profit and revenue records with overall prices growing above 5% each year, an investor might justifiably be worried about the future of the business itself!

But really, this is all a demand story. Supermarket margins haven't declined because there hasn't been much consumer resistance to higher prices. And they're not likely to accept cuts to their margins so long as consumer spending remains robust, giving them little reason to pass on any declines in costs to shoppers.

But I'm optimistic that as inflation comes down largely of its own accord – provided the government doesn't make it worse, or we are hit by another shock – that food prices will gradually become more palatable for households. If we get a slightly more competitive supermarket sector as a result of all this attention, then all the better.

However, I'm also cautious because a lot of what politicians have been saying is less about competition, and more about ensuring farmers get paid. That kind of talk is more commonly associated with protectionism, not competition, which would do consumers a disservice – in fact, it's precisely the opposite of what is needed in a cost-of-living crisis.

Don't get me wrong, I feel for the farmers; I really do. But no one has a right to sell what they want, at the prices they want. If farmers can't sustain their business at market prices, then they should probably sell the farm to someone who can. Perhaps they're not using the land as optimally as they could be; maybe they planted the wrong crops; or perhaps they just got really unlucky? I don't know, and that's the great thing about price discovery and the market process – it tends to sort itself out and minimise waste without anyone, whether it's me, the farmer, or the government, knowing precisely why prices are doing what they're doing.

Whatever eventuates from the spotlight being shone at the big supermarkets, I hope the focus stays firmly on the process. That is, ensuring that we have a competitive market for the benefit of consumers.