A sensible nuclear policy is in the nation's interest

Australia's nuclear energy debate highlights the need for a sensible, economically sound approach to carbon reduction that considers all options, rather than politically-driven policies that may prove inefficient and costly.

Now that the Coalition has formally committed to nuclear power if it wins the next federal election, I think it's worth revisiting the topic (see here and here for my previous thoughts).

First and foremost, I'm not a fan of the Coalition's policy. It's basically 'well you're spending hundreds of billions to pull forward investment in renewables, we're just going to take that and build seven large-scale nuclear plants instead'.

But is that the right option? There's no way to know, because as with Labor's renewables transition (more on that in a bit), there doesn't appear to be so much as a back of the envelope attempt to weigh the costs and benefits of the various approaches and targets.

It didn't have to be this way

The reason nuclear and renewables are even being debated is because we have what economists call an externality, which in this case is unpriced carbon emissions and pollution (coal is extremely dirty). Instead of internalising it by whacking a price on carbon and letting individuals economise where it's most efficient to do so – not necessarily even in the energy sector – our politicians have opted for decades of discretionary policy.

But we were oh so close to getting it right. Recently released Cabinet documents show that back in 2003 the Howard government was advised to implement something close to what economists would consider optimal, an emissions trading scheme:

"The preferred approach to the emissions management strategy centres on introduction of a broad-based market signal.

An emissions trading system offers the ability to achieve the environmental outcome with certainty when and if this becomes an appropriate choice. Emissions trading is recommended as the preferred market system (in comparison to a greenhouse levy) as it provides greater flexibility in the mechanisms available to provide transitional support for industry.

...

[The alternative of] an emphasis on fiscal expenditure could result in costs to the government several fold that of the broad-based market signal, and would have limited scope for revenue generation.

Even a low carbon price would send a strong signal to industry and would affect technology development and uptake."

That plan was scuttled by John Howard himself after "a meeting he had with industry leaders", who persuaded him to preserve their unearned rents (because of the untaxed externality).

Ten years later, a carbon price was introduced by the Gillard government but it was politically vulnerable from the start: Julia Gillard had publicly pledged not to price carbon prior to the 2010 election, only to turn around a year later and say "circumstances have changed". The Coalition ran on that political misstep all the way to the 2013 election, with leader Tony Abbott making "a pledge in blood" to repeal it.

The Coalition then held government for the next nine years, with a carbon price completely off the table: being labelled hypocritical in politics can be fatal. A path-dependent outcome was created, with the Coalition pledging to reach net zero by 2050 through a much more expensive, inefficient "investment" (i.e. spending) strategy. Since forming government, the Albanese government has simply taken the Coalition's framework and broadened it with a heavy focus on renewables.

A third-best option

If a price on carbon is politically impossible there's still a better approach than the ones taken by the Albanese government and Peter Dutton.

That approach would be to legalise nuclear power and level the playing field between the various sources of energy generation. Such a policy would include coercing/paying the states to remove their nuclear bans and ease roadblocks to construction (including for renewables!), establishing a building-friendly regulatory framework that would allow nuclear power to face a fair market test (i.e. more Korean or Indian than post-1970s American), remove subsidies for renewables (including for all the additional transmission lines required), appropriately tax the harms caused by coal and gas (just don't call it a carbon tax!), and get on with it.

Nuclear would then be an option. Not necessarily seven plants, or even one. But investors would be allowed to start looking into it.

I mean, there's no ideological reason for the nuclear ban within Labor or the Coalition, other than perhaps Labor's ties to the Greens, the party for whom if climate change were a forest fire would insist that we fight it with nothing but buckets of water. But the recently-elected UK Labour government committed to supporting nuclear, suggesting centre-left governments can get behind it:

"Labour will end a decade of dithering that has seen the Conservatives duck decisions on nuclear power. We will ensure the long-term security of the sector, extending the lifetime of existing plants, and we will get Hinkley Point C over the line. New nuclear power stations, such as Sizewell C, and Small Modular Reactors, will play an important role in helping the UK achieve energy security and clean power while securing thousands of good, skilled jobs."

Alas, instead of being open to the idea of nuclear – or simply not ruling it out – the Albanese Labor government has gone all-in against it, making nuclear a fully partisan issue in Australia. So when Dutton formally announced the Coalition's nuclear policy, Labor responded with... memes:

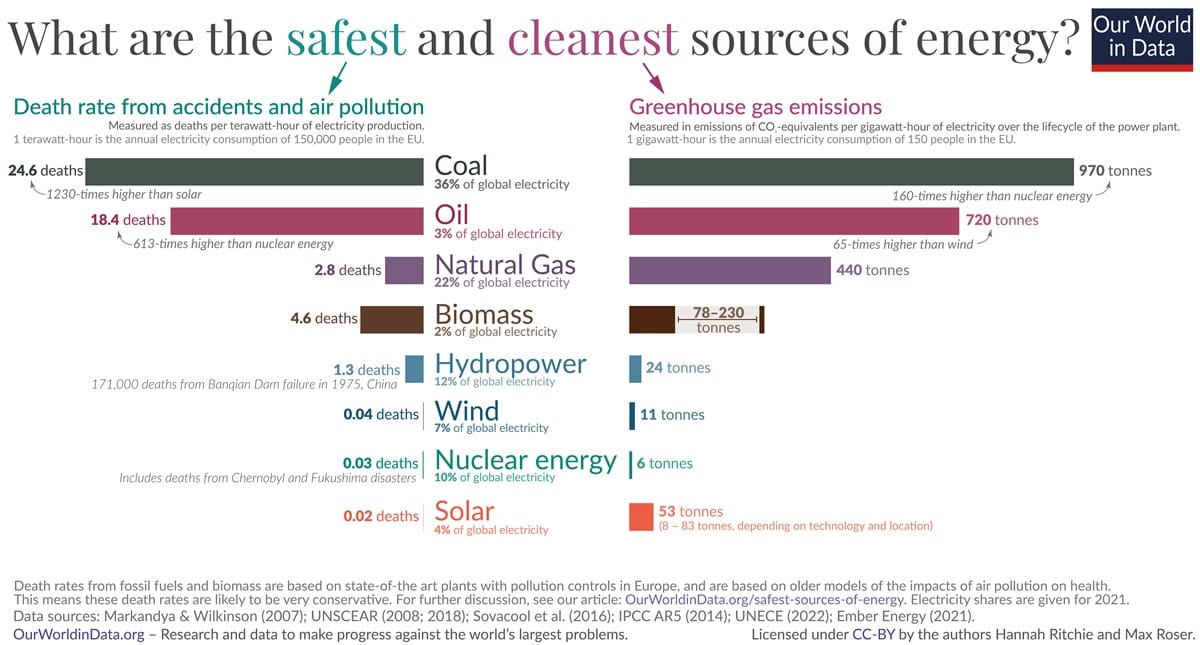

That's despite nuclear being one of the safest, cleanest forms of energy available:

As the Coalition did with a price on carbon, Labor has taken a stand against nuclear no matter what the evidence suggests. But as former Chief Scientist Alan Finkel wrote, there's no good reason to be the only G20 country to ban one of the world's best potential sources of energy:

"Still, introducing nuclear power when we can, starting in the 2040s, would bring benefits. Most importantly, nuclear power generation would reduce the ongoing mining footprint for the regular replacement of solar panels, wind turbines and batteries and the expanded electricity generation to support decarbonising our exports and population growth.

For these reasons, it would be worth removing the ban on nuclear power so that we can at least thoroughly investigate the options."

If nuclear remains banned, people won't investigate it because there's no potential pay-off. Perhaps small modular reactors are the answer and become viable in a decade or two. Perhaps thorium-based reactors are the go. But if they're all illegal, we'll never know and no one will even be looking.

Dutton's plan is half-baked

Poland's government is planning to use nuclear to replace its aging coal plants (so, a policy similar to Duttons). But it's also passing "a law that would free up investments in onshore wind farms" by removing various restrictions.

Those sort of progressive moves are completely absent from Dutton's plan; it shouldn't be nuclear or renewables but nuclear and renewables. To borrow from Deng Xiaoping, "it doesn't matter whether a cat is black or white, as long as it catches mice". Australia needs a policy that frees up competitive forces and sees us build the most efficient energy generation (which considers cost and reliability) for our needs.

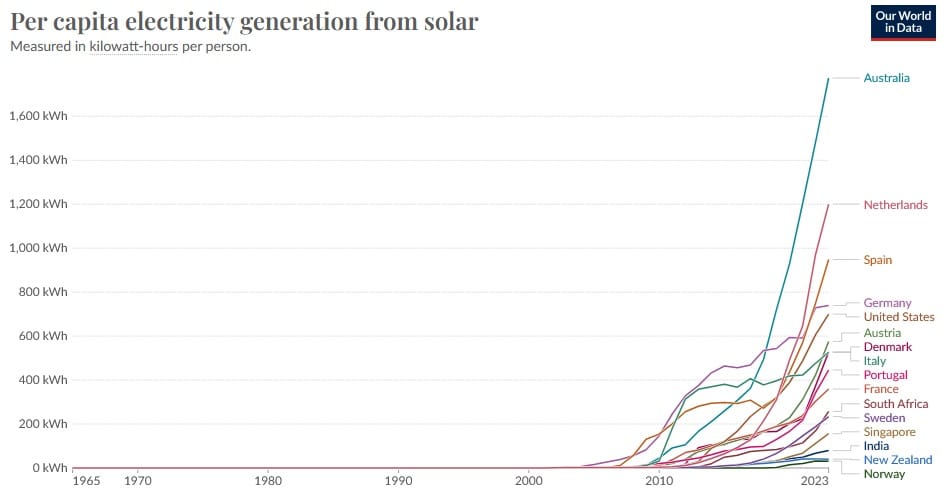

It may well be that nuclear isn't suitable for Australia. Thanks to China's excessive investment in solar panel manufacturing, rooftop subsidies, and a lack of domestic competition crying for protection, we're the world leader in solar.

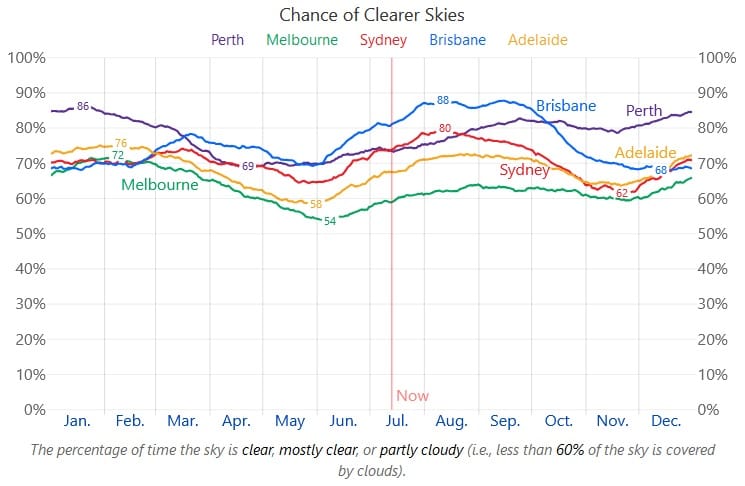

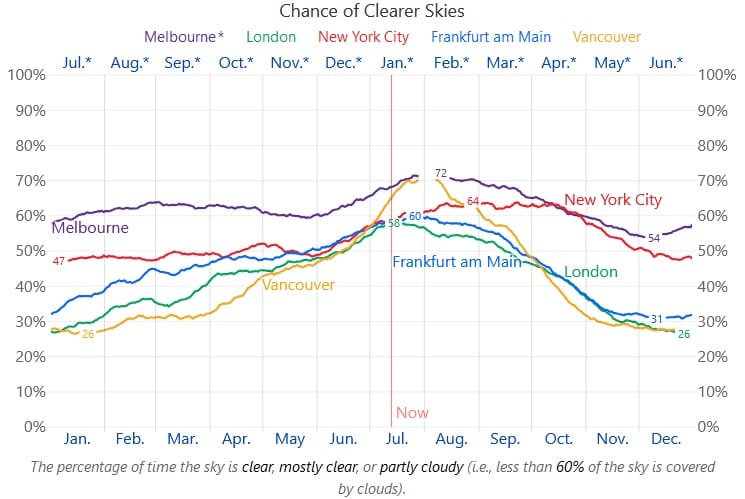

We're also fortunate that in most of Australia, the sun shines a lot. Even Melbourne on the worst day of the year has a 54% chance of clear skies.

Melbourne might look gloomy compared to other Australian cities, but it's more likely to see year-round sun than many northern hemisphere cities.

Perhaps the combination of solar, batteries – which continue to fall in price – and domestic gas to 'firm' up supply during peak periods is optimal for Australia. If it is, then Dutton's nuclear plan could end up wasting even more resources than Albanese's renewables push.

It's about more than just cost

A word that hasn't received enough attention in this debate has been reliability. Renewables can be cheap but that cheapness comes at the cost of reliability. In a review of possible scenarios to being carbon neutral by 2050, France's electricity provider (RTE) found that a 100% renewables scenario was more expensive than nuclear because it's harder to achieve a socially desirably level of reliability than it would be with nuclear still in the mix. A comparison purely based on estimated future energy generation costs, such as CSIRO's GenCost, can therefore be misleading:

"The terms for comparing the economic attributes of the two energies have evolved. Historical nuclear has been very competitive and remains so today, but the cost of third-generation reactors has increased, while that of renewables has decreased. However, the very characteristics of wind and solar power make it impossible to reach a conclusion based solely on a comparison of production costs: the variability of production must be compensated by flexible resources, and their integration into the system requires grid reinforcement. Discussions must therefore compare the full cost of these different options ('system costs') rather than just the cost of the technologies individually."

Energy security and reliability are important. Western Australia maintains a gas reservation policy, despite it being economically wasteful, because it ensures grid reliability. Nuclear is more expensive than pure renewables, but if we want to move away from coal and maintain grid reliability, then it becomes competitive. Griffith University's Magnus Söderberg recently made precisely that point:

"Nuclear power plants produce power at a fairly steady pace, which leads to a more steady market price. Power systems built around wind and solar produce cheaper power, but with more uncertain output and much greater variability in price.

This greater variability can be smoothed to some extent by adding storage such as pumped hydro and large-scale batteries, but to the extent that it remains, uncertain prices make investments in power-hungry projects harder to justify.

The greater the uncertainty, the more investment moves to other firms, other less energy-intensive industries and other countries."

There's a reason why AI companies are rushing to cut deals with nuclear power generators, rather than solar farms supported with batteries and natural gas. Data centres need "firm", i.e. reliable, power. Renewables may not cut it for certain industries.

Why the rush?

One question that has been bothering me since the renewables target was announced is: why are we rushing to transition our entire grid to renewables before we're good and ready?

From what I gather, the Albanese government's target to have a grid containing 82% renewables by 2030 appears to be almost completely arbitrary, flowing from a speech Albo gave in December 2021 that was picked up by "many journalists and lobby groups", and was then adopted by the government itself.

Policymaking at its finest!

Now that it's an implicit target – while not legislated, the Albanese government would lose credibility if it backtracked – it means this government will try to achieve it come hell or high water. But as the Australian Energy Council warned, that has consequences:

"The downside to all this is, of course, politicisation – bureaucracies and policymakers may implement inefficient policies to meet what is ultimately an arbitrary figure."

The Albanese government will almost certainly miss its 2030 target, given that the same obstructionism that is so prevalent with housing also exists for large-scale solar, wind and the tens of thousands of kilometres in additional transmission lines that are needed to connect it all. The lack of formal legislation means that a Dutton government would just abandon it entirely.

But it's all just a distraction; who's to say that the energy grid is the best place to reduce our carbon emissions? Perhaps we should be doing a Denmark and taxing our cows €96/year, increasing to €240/year by 2035? I jest, but without a price on carbon those are the sort of decisions that have to be made.

Once again I'm back to the lack of prices, which means both parties are just prodding in the dark – making educated guesses with a sprinkle of politicisation, i.e. achieving net zero with a bunch of costly side-goals such as 'green jobs' and 'renewables targets' tacked on.

Last week the former chair of the ACCC, Rod Sims, was similarly disgruntled:

"It is a shame that there is no embrace of the first best policy to get to net-zero electricity: putting a price on the damage caused by carbon emissions. Then we could allow various options to compete and the market to get us to where we need to go. Without a carbon price, however, we are left not with a market-determined decision but one dictated by government."

Where I differ from Sims is with his claim that "renewables plus the many available options to firm them are the clear choice for Australia".

Perhaps a grid powered by 82% renewables firmed with gas is desirable by 2030. Or maybe it's 80% by 2040, or just 70% by 2050, and we're overpaying by a considerable margin to pull the transition forward with aggressive subsidies.

As the saying goes, there's more than one way to skin a cat. A price on carbon would see us take the least-cost approach to achieving the government's emissions reduction target. For all we know, transitioning our grid to 82% renewables by 2030 might be the 1st, 10th, or 50th best way of doing the same thing. Maybe nuclear and a cow tax would be better? No one can know for sure.

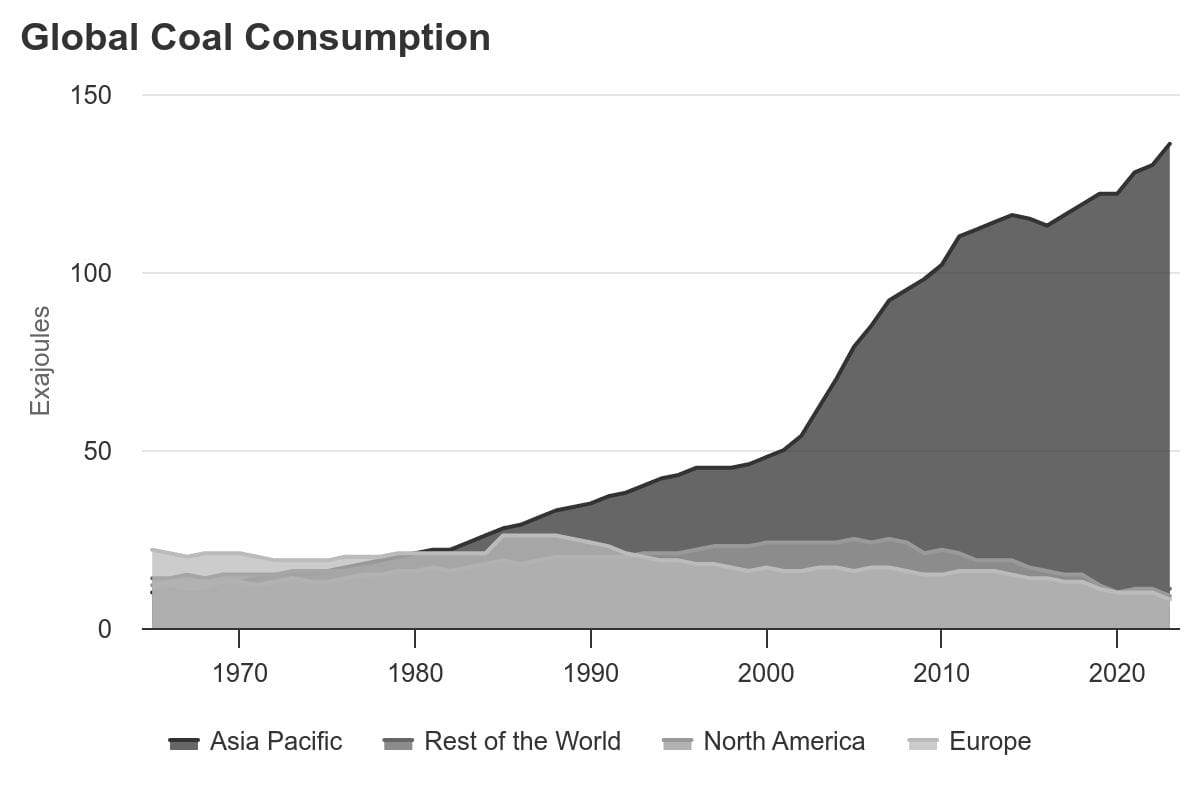

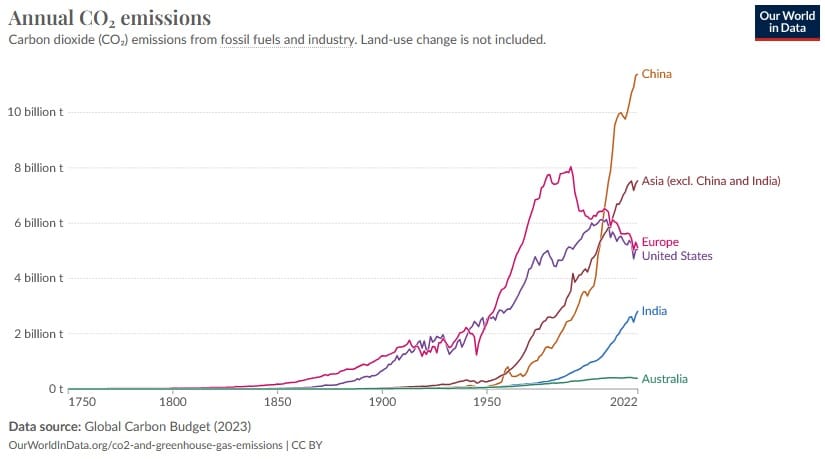

But what I do know is that we're paying a potentially high price to transition our grid to renewables while actively blocking a potentially viable alternative. And I get that our politicians probably want to strut their stuff at global conferences showing pictures of all our pretty solar and wind farms, but for all the debate – all the controversy and partisan politics – what happens to the world's carbon emissions is going to be determined elsewhere:

By all means we should do our part and lead by example, but we also need to be mindful of the trade-offs. That's especially important in the energy sector given its strong correlation with economic well-being. Renewables might well be best for Australia, but it's hard to take the argument seriously when potential competitors are legally forbidden. A more sensible energy policy would be to legalise nuclear power and level the playing field between the various sources of energy generation, so that the least-cost (after pricing externalities) method can be deployed.